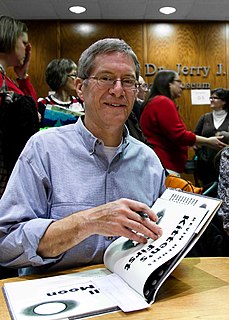

A Quote by Kevin Henkes

When I work on a novel, I usually have one character and a setting in mind.

Related Quotes

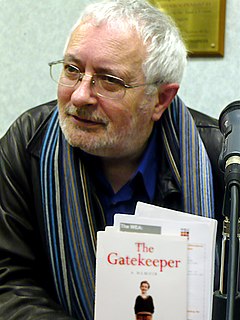

o matter how much research you do, or invention you do, whether it's a character from a novel, a completely invented character or someone who actually existed, it's a work of faction. By the very fact you only have an hour and a half or two hours to tell a story, you're telescoping events and it is, in the end, a work of imagination.

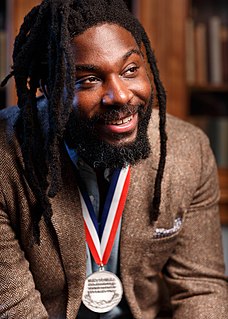

I believe that every character is a setting, a world with moving parts, and on the other hand, every setting is, in fact, a character - a living breathing thing with personality and backstory. The way stories come to life, at least for me, is when these elements commune in relationship to one another.

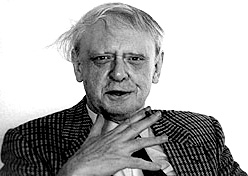

The most common mistake students of literature make is to go straight for what the poem or novel says, setting aside the way that it says it. To read like this is to set aside the ‘literariness’ of the work – the fact that it is a poem or play or novel, rather than an account of the incidence of soil erosion in Nebraska.

There is, in fact, not much point in writing a novel unless you can show the possibility of moral transformation, or an increase in wisdom, operating in your chief character or characters. Even trashy bestsellers show people changing. When a fictional work fails to show change, when it merely indicates that human character is set, stony, unregenerable, then you are out of field of the novel and into that of the fable or the allegory. - from the introduction of the 1986 Norton edition