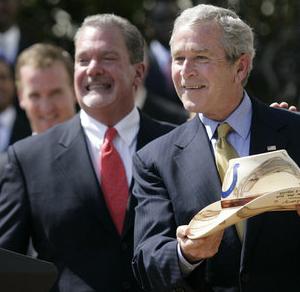

A Quote by Kevin Kwan

I have a photographic memory.

Quote Topics

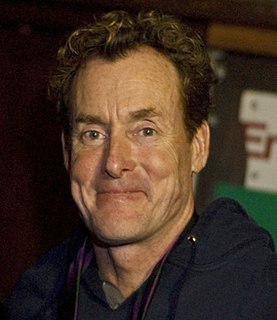

Related Quotes

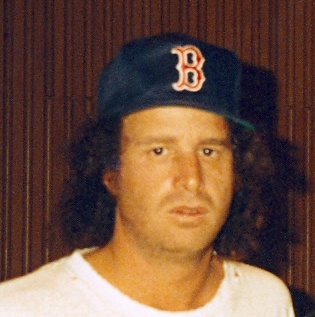

My father was famous for his photographic memory. He was in the OSS. They trained him to be captured on purpose and to read upside down and backwards and commit to memory every document in Germany he saw as he was being interrogated - every schedule on every wall. So, that photographic memory somehow made its way to me when I was young.

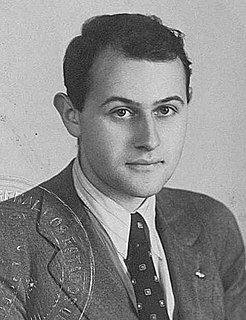

Photographic memory is often confused with another bizarre - but real - perceptual phenomenon called eidetic memory, which occurs in between 2 and 15 percent of children and very rarely in adults. An eidetic image is essentially a vivid afterimage that lingers in the mind's eye for up to a few minutes before fading away.