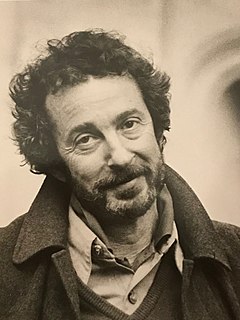

A Quote by Kevin Sessums

I don't write poetry for the New Yorker. My poems appear in the Nation, mostly.

Related Quotes

I believe it's impossible to write good poetry without reading. Reading poetry goes straight to my psyche and makes me want to write. I meet the muse in the poems of others and invite her to my poems. I see over and over again, in different ways, what is possible, how the perimeters of poetry are expanding and making way for new forms.

Some of Mr. Gregory's poems have merely appeared in The New Yorker ; others are New Yorker poems: the inclusive topicality, the informed and casual smartness, the flat fashionable irony, meaningless because it proceeds from a frame of reference whose amorphous superiority is the most definite thing about it they are the trademark not simply of a magazine but of a class.

I would read the Shel Silverstein poems, Dr. Seuss, and I noticed early on that poetry was something that just stuck in my head and I was replaying those rhymes and try to think of my own. In English, the only thing I wanted to do was poetry and all the other kids were like, "Oh, man. We have to write poems again?" and I would have a three-page long poem. I won a national poetry contest when I was in fourth grade for a poem called "Monster In My Closet.

I think that anyone who likes writing views 'The New Yorker' as the, you know, pinnacle of the publishing world. If you get 50 words published in 'The New Yorker,' it's more important than 50 articles in other places. So, would I love to one day write for them? I guess. But that's not my sole ambition.

If I'm still wistful about On the Road, I look on the rest of the Kerouac oeuvre--the poems, the poems!--in horror. Read Satori in Paris lately? But if I had never read Jack Kerouac's horrendous poems, I never would have had the guts to write horrendous poems myself. I never would have signed up for Mrs. Safford's poetry class the spring of junior year, which led me to poetry readings, which introduced me to bad red wine, and after that it's all just one big blurry condemned path to journalism and San Francisco.

Another example of what I have to put up with from him. But there was a time I was mad at all my straight friends when AIDS was at its worst. I particularly hated the New Yorker, where Calvin [Trillin] has published so much of his work. The New Yorker was the worst because they barely ever wrote about AIDS. I used to take out on Calvin my real hatred for the New Yorker.