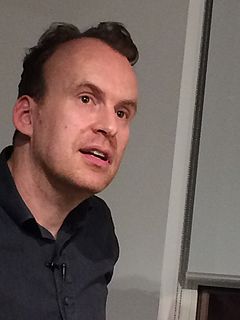

A Quote by Konnie Huq

My A-levels were physics, chemistry and maths. Science is fascinating but I wouldn't say I have used it since then. I decided to do economics.

Related Quotes

Religion and science, for example, are often though to be opponents, but as I have shown, the insights of ancient religions and of modern science are both needed to reach a full understanding of human nature and the conditions of human satisfaction. The ancients may have known little about biology, chemistry, physics, but many were good psychologists.