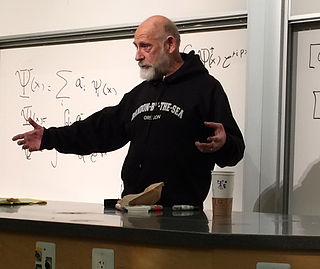

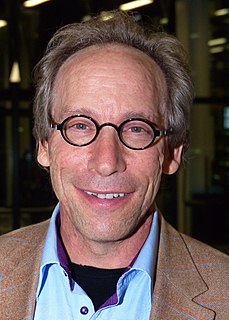

A Quote by Leonard Susskind

I often feel a discomfort, a kind of embarrassment, when I explain elementary-particle physics to laypeople. It all seems so arbitrary - the ridiculous collection of fundamental particles, the lack of pattern to their masses.

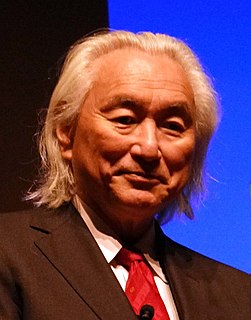

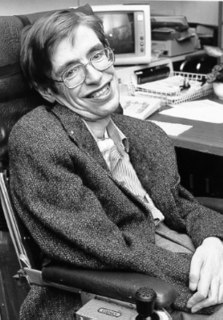

Related Quotes

Three principles - the conformability of nature to herself, the applicability of the criterion of simplicity, and the utility of certain parts of mathematics in describing physical reality - are thus consequences of the underlying law of the elementary particles and their interactions. Those three principles need not be assumed as separate metaphysical postulates. Instead, they are emergent properties of the fundamental laws of physics.

The world of science lives fairly comfortably with paradox. We know that light is a wave, and also that light is a particle. The discoveries made in the infinitely small world of particle physics indicate randomness and chance, and I do not find it any more difficult to live with the paradox of a universe of randomness and chance and a universe of pattern and purpose than I do with light as a wave and light as a particle. Living with contradiction is nothing new to the human being.

The only difference between causation and the value is that the word "cause" implies absolute certainty whereas the implied meaning of "value" is one of preference. In classical science it was supposed that the world always works in terms of absolute certainty and that "cause" is the more appropriate word to describe it. But in modern quantum physics all that is changed. Particles "prefer" to do what they do. An individual particle is not absolutely committed to one predictable behavior. What appears to be an absolute cause is just a very consistent pattern of preferences.

The standard model of particle physics says that the universe consists of a very small number of particles, 12, and a very small number of forces, four. If we're correct about those 12 particles and those four forces and understand how they interact, properly, we have the recipe for baking up a universe.