A Quote by Lord Chesterfield

Montesquieu well knew, and justly admired, the happy constitution of this country [Great Britain], where fixed and known laws equally restrain monarchy from tyranny and liberty from licentiousness.

Related Quotes

In the Laws it is maintained that the best constitution is made up of democracy and tyranny, which are either not constitutions at all, or are the worst of all. But they are nearer the truth who combine many forms; for the constitution is better which is made up of more numerous elements. The constitution proposed in the Laws has no element of monarchy at all; it is nothing but oligarchy and democracy, leaning rather to oligarchy.

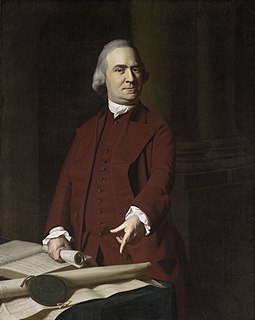

Just and true liberty, equal and impartial liberty, in matters spiritual and temporal is a thing that all men are clearly entitled to by the eternal and immutable laws of God and nature, as well as by the laws of nations and all well-grounded and municipal laws, which must have their foundation in the former.

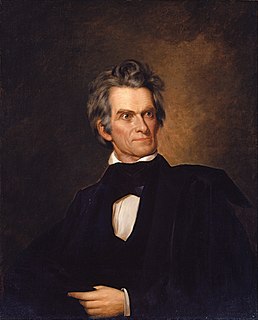

We are descended from a people whose government was founded on liberty; our glorious forefathers of Great Britain made liberty the foundation of everything. That country is become a great, mighty, and splendid nation; not because their government is strong and energetic, but, sir, because liberty is its direct end and foundation.

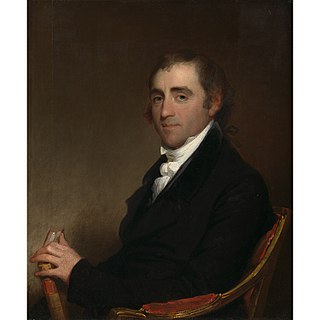

History will also give occasion to expatiate on the advantage of civil orders and constitutions; how men and their properties are protected by joining in societies and establishing government; their industry encouraged and rewarded, arts invented, and life made more comfortable; the advantages of liberty, mischiefs of licentiousness, benefits arising from good laws and a due execution of justice. Thus may the first principles of sound politics be fixed in the minds of youth.

The laws are, and ought to be, relative to the constitution, and not the constitution to the laws. A constitution is the organization of offices in a state, and determines what is to be the governing body, and what is the end of each community. But laws are not to be confounded with the principles of the constitution; they are the rules according to which the magistrates should administer the state, and proceed against offenders.

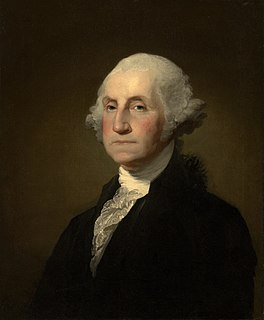

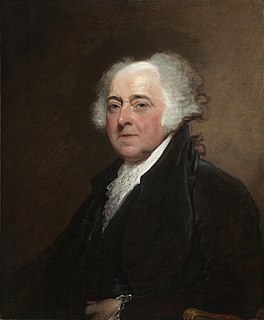

If Aristotle, Livy, and Harrington knew what a republic was, the British constitution is much more like a republic than an empire. They define a republic to be a government of laws, and not of men. If this definition is just, the British constitution is nothing more or less than a republic, in which the king is first magistrate. This office being hereditary, and being possessed of such ample and splendid prerogatives, is no objection to the government's being a republic, as long as it is bound by fixed laws, which the people have a voice in making, and a right to defend.

Were I to define the British constitution, therefore, I should say, it is a limited monarchy, or a mixture of the three forms of government commonly known in the schools, reserving as much of the monarchical splendor, the aristocratical independency, and the democratical freedom, as are necessary that each of these powers may have a control, both in legislation and execution, over the other two, for the preservation of the subject's liberty.