A Quote by Louise Bernikow

What is commonly called literary history is actually a record of choices.

Related Quotes

What are your choices? Whom are your choices for? Not just for yourself. Chose now whom you will serve, and that choice is going to affect the next generation, and the next generation, and the next. Choice never affects just one person alone. It goes on and on and the effect goes out into geography and history. You are part of history and your choices become part of history.

Through the history of my records, from when I started controlling the visual, I always used lower case letters for everything, I can't even explain why that is. The character is actually me, and I think once you see the film for the record, or see the video or really get in to the record, that will all sort of reveal itself to you.

The Booker thing was a catalyst for me in a bizarre way. It’s perceived as an accolade to be published as a ‘literary’ writer, but, actually, it’s pompous and it’s fake. Literary fiction is often nothing more than a genre in itself. I’d always read omnivorously and often thought much literary fiction is read by young men and women in their 20s, as substitutes for experience.

Let us record the atoms as they fall upon the mind in the order in which they fall, let us trace the pattern, however disconnected and incoherent in appearance, which each sight or incident scores upon the consciousness. Let us not take it for granted that life exists more fully in what is commonly thought big than in what is commonly thought small.

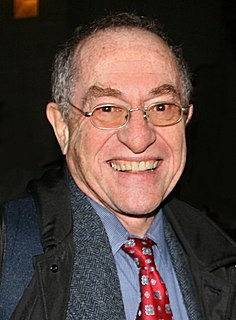

When I was growing up, my mother would always say, 'It will go on your permanent record.' There was no 'permanent record.' If there were a 'permanent record,' I'd never be able to be a lawyer. I was such a bum, in elementary school and high school... There is a permanent record today and it's called the Internet.

When I was growing up, my mother would always say, 'It will go on your permanent record.' There was no 'permanent record.' If there were a 'permanent record,' I'd never be able to be a lawyer. I was such a bum in elementary school and high school... There is a permanent record today, and it's called the Internet.

I hold all knowledge that is concerned with things that actually exist - all that is commonly called Science - to be of very slight value compared to the knowledge which, like philosophy and mathematics, is concerned with ideal and eternal objects, and is freed from this miserable world which God has made.