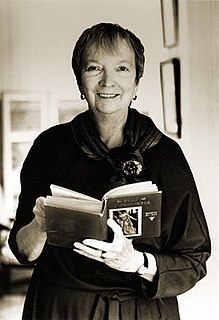

A Quote by Madeleine L'Engle

In your language you have a form of poetry called the sonnet…There are fourteen lines, I believe, all in iambic pentameter. That’s a very strict rhythm or meter…And each line has to end with a rigid pattern. And if the poet does not do it exactly this way, it is not a sonnet…But within this strict form the poet has complete freedom to say whatever he wants…You’re given the form, but you have to write the sonnet yourself. What you say is completely up to you.

Related Quotes

When you work in form, be it a sonnet or villanelle or whatever, the form is there and you have to fill it. And you have to find how to make that form say what you want to say. But what you find, always--I think any poet who's worked in form will agree with me--is that the form leads you to what you want to say.

To write poetry is to be very alone, but you always have the company of your influences. But you also have the company of the form itself, which has a kind of consciousness. I mean, the sonnet will simply tell you, that's too many syllables or that's too many lines or that's the wrong place. So, instead of being alone, you're in dialogue with the form.

A sermon is a form that yields a certain kind of meaning in the same way that, say, a sonnet is a form that deals with a certain kind of meaning that has to do with putting things in relation to each other, allowing for the fact of complexity reversal, such things. Sermons are, at their best, excursions into difficulty that are addressed to people who come there in order to hear that.