A Quote by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio

The winter oak... is very useful in buildings but when in a moist place it takes in water to its centre... and so it rots. The Turkey oak and the beech both... take in moisture to their centre and soon decay. White and black poplar, as well as willow, linden, and the agnus castus... are of great service from their stiffness... they are a convenient material to use in carving.

Related Quotes

Our own economy tells us to take as much as we can get, right? Our own economy says, you're going to be the most successful graduate if you go into the business world and take as much you can get. That's not how nature works. Nature has a much simpler economy. Everything in nature takes what it needs. That's it. You don't see an oak tree gathering up all the resources. An oak tree takes what it needs to be the authentic oak tree it is.

Time is different for a tree than for a man. Sun and soil and water, these are the things a weirwood understands, not days and years and centuries. For men, time is a river. We are trapped in its flow, hurtling from past to present, always in the same direction. The lives of trees are different. They root and grow and die in one place, and that river does not move them. The oak is the acorn, the acorn is the oak.

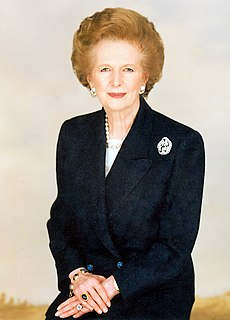

The right-of-centre parties still often compete with left-of-centre ones to proclaim their attachment to all the main programmes of spending, particularly spending on social services of one kind or another. But this foolish as well as muddled. It is foolish because left-of-centre parties will always be able to outbid right-of-centre ones in this auction - after all, that is why they are on the left in the first place. The muddle arises because once we concede that public spending and taxation are than a necessary evil we have lost sight of the core values of freedom.

Society is an illusion to the young citizen. It lies before him in rigid repose, with certain names, men, and institutions, rootedlike oak-trees to the centre, round which all arrange themselves the best they can. But the old statesman knows that society is fluid; there are no such roots and centres; but any particle may suddenly become the centre of the movement, and compel the system to gyrate round it, as every man of strong will, like Pisistratus, or Cromwell, does for a time, and every man of truth, like Plato, or Paul, does forever.