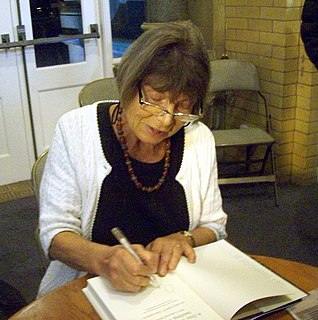

A Quote by Margaret Drabble

I'd rather be at the end of a dying tradition, which I admire, than at the beginning of a tradition which I deplore.

Related Quotes

The book [Saving Calvinism] argues in each case that the Reformed tradition is broader and deeper than we might think at first glance - not that there are people on the margins of the tradition saying crazy things we should pay attention to, but rather that there are resources within the "mainstream" so to speak, which give us reason to think that the tradition is nowhere near as doctrinally narrow as the so-called "Five Points of Calvinism" might lead one to believe.

Those who feel guilty contemplating "betraying" the tradition they love by acknowledging their disapproval of elements within it should reflect on the fact that the very tradition to which they are so loyal—the "eternal" tradition introduced to them in their youth—is in fact the evolved product of many adjustments firmly but delicately made by earlier lovers of the same tradition.

When tradition is thought to state the way things really are, it becomes the director and judge of our lives; we are, in effect, imprisoned by it. On the other hand, tradition can be understood as a pointer to that which is beyond tradition: the sacred. Then it functions not as a prison but as a lens.

The urge to break with a tradition is only appropriate when you're dealing with an outdated, troublesome tradition: I never really thought about that because I take the old-fashioned approach of equating tradition with value (which may be a failing). But whatever the case, positive tradition can also provoke opposition if it's too powerful, too overwhelming, too demanding. That would basically be about the human side of wanting to hold your own.

God is not good, or wise, or intelligent anyway that we know. So, people like Maimonides in the Jewish tradition, Eboncina in the Muslim tradition, Thomas Aquinas in the Christian tradition, insisted that we couldn't even say that God existed because our concept of existence is far too limited and they would have been horrified by the ease with which we talk about God today.