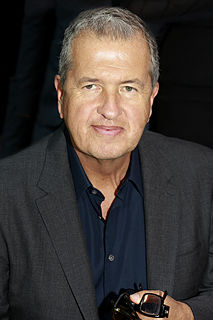

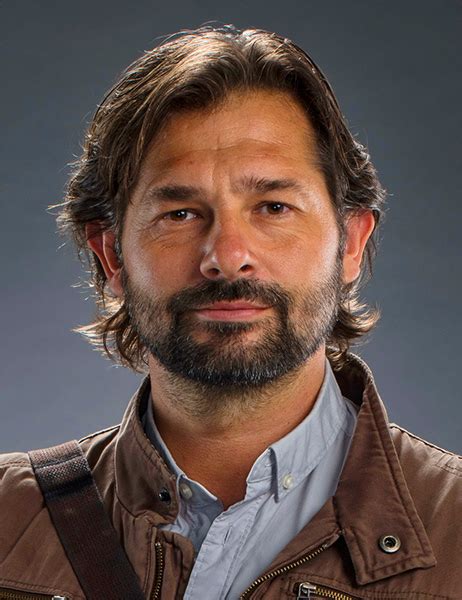

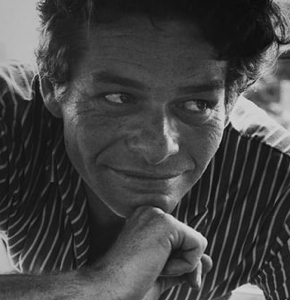

A Quote by Mario Testino

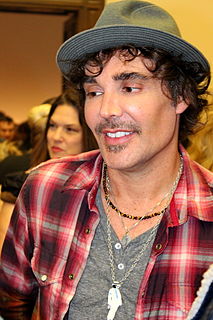

Grunge came from a group of English photographers, and they were documenting their own reality... I'm South American - we celebrate life.

Related Quotes

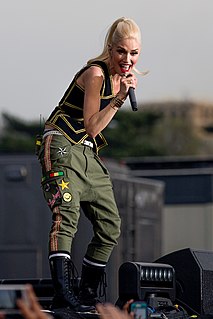

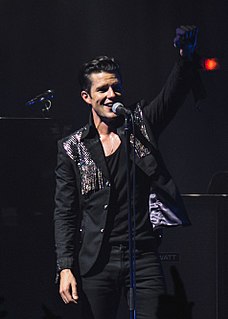

Actually, my first group was a folkloric group, an Argentine folkloric group when I was 10. By the time I was 11 or 12 I started writing songs in English. And then after a while of writing these songs in English it came to me that there was no reason for me to sing in English because I lived in Argentina and also there was something important [about Spanish], so I started writing in Spanish.

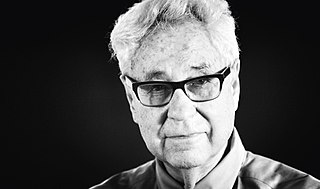

I have dear friends in South Carolina, folks who made my life there wonderful and meaningful. Two of my children were born there. South Carolina's governor awarded me the highest award for the arts in the state. I was inducted into the South Carolina Academy of Authors. I have lived and worked among the folks in Sumter, South Carolina, for so many years. South Carolina has been home, and to be honest, it was easier for me to define myself as a South Carolinian than even as an American.

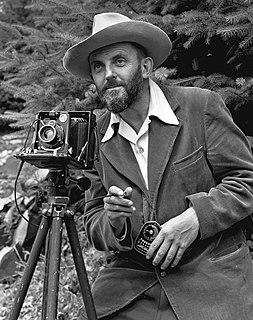

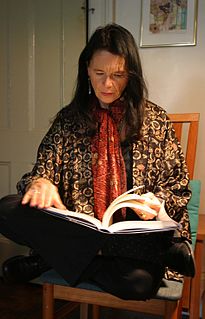

My mother actually left American in 1929 to be part of an alternative community of bohemians around her then father-in-law who was a well-known Greek poet. This group of people were living in this semi-Luddite reality and weaving their own clothes - proto-hippies in a way- -but around an artistic vision.