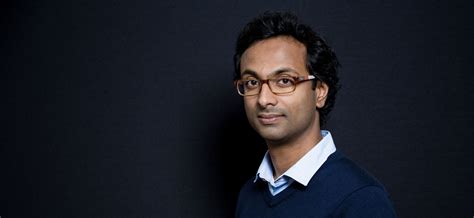

A Quote by Mark Leibovich

I work for a big newspaper, and I guess I'm an insider. I don't have the luxury of calling myself a foreign correspondent and just swooping in and then leaving.

Related Quotes

I don't ever think of myself as coming from a particular class because my father was working class but made his living as a newspaper foreign correspondent - someone of no fixed abode, as he used to say - who was as comfortable dining with the Mountbattens in India as he was having a pint with the boys. He was very gregarious.

The endeavor of being a foreign correspondent means that you will never be their equal. And that has its pros and cons. Were you to be an insider in a particular society, then you would be one of them, and the way you would write about that society would be very different. When you're brought up in a certain way, you have certain blind spots to the things going on in your culture. There is an illumination the outsider brings to a place or a situation that cannot be duplicated.

Like all young reporters - brilliant or hopelessly incompetent - I dreamed of the glamorous life of the foreign correspondent: prowling Vienna in a Burberry trench coat, speaking a dozen languages to dangerous women, narrowly escaping Sardinian bandits - the usual stuff that newspaper dreams are made of.

In my former life I was in insider, as much as anybody else. And I knew what it's like, and I still know what it's like to be an insider. It's not bad, it's not bad. Now I'm being punished for leaving the special club and revealing to you the terrible things that are going on having to do with America. Because I used to be part of the club, I'm the only one that can fix it.

I got married three days after graduation, and the first thing I did what I was expected to do which was to work on a small newspaper. So we were in Chicago where my husband worked for the Chicago Sun-Times and we were having dinner with his editor and he said 'So what are you 'gonna do honey?' and I said 'I'm going to work on a newspaper', and he said 'I don't think so", because Newspaper Guild regulations said that I couldn't work on the same newspaper as my husband.