A Quote by Martin Amis

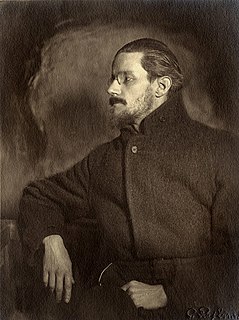

What did Nabokov and Joyce have in common, apart from the poor teeth and the great prose? Exile, and decades of near pauperism.

Related Quotes

What did Nabokov and Joyce have in common, apart from the poor teeth and the great prose? Exile, and decades of near pauperism. A compulsive tendency to overtip. An uxoriousness that their wives deservedly inspired. More than that, they both lived their lives 'beautifully'--not in any Jamesian sense (where, besides, ferocious solvency would have been a prerequisite), but in the droll fortitude of their perseverance. They got the work done, with style.

I've been working hard on [Ulysses] all day," said Joyce. Does that mean that you have written a great deal?" I said. Two sentences," said Joyce. I looked sideways but Joyce was not smiling. I thought of [French novelist Gustave] Flaubert. "You've been seeking the mot juste?" I said. No," said Joyce. "I have the words already. What I am seeking is the perfect order of words in the sentence.

When you're missing your two front teeth, that's honesty. That is a door to your oral history. You're not covering anything up. You're saying, 'Hey world, I'm missing my front teeth. I'm gross; I'm dirty; I'm poor. I clearly have no problem with public urination and eating garbage. Don't come near me, I'll gum you to death!

A friend came to visit James Joyce one day and found the great man sprawled across his writing desk in a posture of utter despair. James, what’s wrong?' the friend asked. 'Is it the work?' Joyce indicated assent without even raising his head to look at his friend. Of course it was the work; isn’t it always? How many words did you get today?' the friend pursued. Joyce (still in despair, still sprawled facedown on his desk): 'Seven.' Seven? But James… that’s good, at least for you.' Yes,' Joyce said, finally looking up. 'I suppose it is… but I don’t know what order they go in!

What a lumbering poor vehicle prose is for the conveying of a great thought! ... Prose wanders around with a lantern & laboriously schedules & verifies the details & particulars of a valley & its frame of crags & peaks, then Poetry comes, & lays bare the whole landscape with a single splendid flash.

Mann and Joyce are very different, and yet their fiction often appeals to the same people: Harry Levin taught a famous course on Joyce, Proust, and Mann, and Joseph Campbell singled out Joyce and Mann as special favorites. To see them as offering "possibilities for living", as I do, isn't to identify any distinctive commonality. After all, many great authors would fall under that rubric.

Probably all of us, writers and readers alike, set out into exile, or at least into a certain kind of exile, when we leave childhood behind...The immigrant, the nomad, the traveler, the sleepwalker all exist, but not the exile, since every writer becomes an exile simply by venturing into literature, and every reader becomes an exile simply by opening a book.