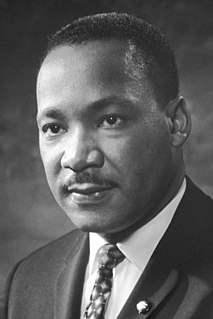

A Quote by Martin Luther King, Jr.

You are resisting, but you've come to see that tactically as well as morally, it is better to be nonviolent.If one would, didn't want to deal with the moral questions, it would just be impractical for the Negro to talk about making his struggle a violent one.

Related Quotes

In the event of a violent revolution, we would be sorely outnumbered. And when it was all over, the Negro would face the same unchanged conditions, the same squalor and deprivation-the only difference being that his bitterness would be even more intense, his disenchantment even more abject. Thus, in purely practical as well as moral terms, the American Negro has no rational alternative to nonviolence.

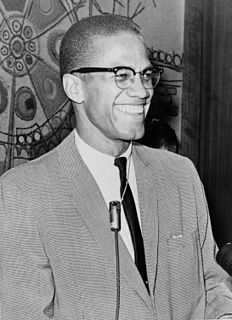

I myself would go for nonviolence if it was consistent, if everybody was going to be nonviolent all the time. I'd say, okay, let's get with it, we'll all be nonviolent. But I don't go along with any kind of nonviolence unless everybody's going to be nonviolent. If they make the Ku Klux Klan nonviolent, I'll be nonviolent. If they make the White Citizens Council nonviolent, I'll be nonviolent. But as long as you've got somebody else not being nonviolent, I don't want anybody coming to me talking any nonviolent talk.

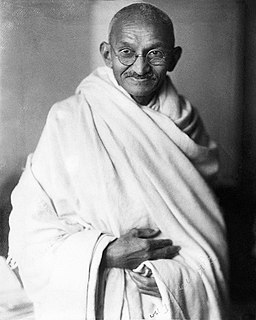

Years ago I was asked this question: Do terrorists fear anything? I said, 'I suspect they would fear a morally strong America.' They would know that a morally strong America would not be dislodged. You can always appeal to a point of vulnerability which would break a people up. [Terrorists] don't fear so much the weaponry as the moral courage, and I think a morally strong America would be intimidating to them.

If she took Po as her husband, she would be making promises about a future she couldn't yet see. For once she became his wife, she would be his forever. And, no matter how much freedom Po gave her, she would always know that it was a gift. Her freedom would be not be her own; it would be Po's to give or to withhold. That he never would withhold it made no difference. If it did not come from her, it was not really hers.

I prize the purity of his character as highly as I do that of hers. As a moral being, whatever it is morally wrong for her to do,it is morally wrong for him to do. The fallacious doctrine of male and female virtues has well nigh ruined all that is morally great and lovely in his character: he has been quite as deep a sufferer by it as woman, though mostly in different respects and by other processes.

The Master was exceedingly gracious to university dons who visited him, but he would never reply to their questions or be drawn into their theological speculations. To his disciples, who marveled at this, he said, "Can one talk about the ocean to a frog in a well or about the divine to people who are restricted by their concepts?