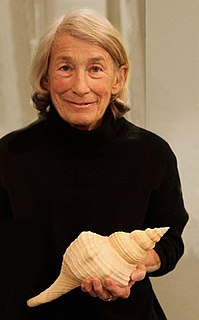

A Quote by Mary Oliver

I read Rumi, the 13th-century Persian poet, every day.

Related Quotes

My first advice would be to read, read, read, which sounds interesting coming in a digital age, but it's so much easier to listen to a poem than it is to sit down and actually read it and to hear it in your head and that is something that every poet or aspiring poet needs to be able to do, I think to hear it in their head.

For the Persian poet Rumi, each human life is analogous to a bowl floating on the surface of an infinite ocean. As it moves along, it is slowly filling with the water around it. That's a metaphor for the acquisition of knowledge. When the water in the bowl finally reaches the same level as the water outside, there is no longer any need for the container, and it drops away as the inner water merges with the outside water. We call this the moment of death. That analogy returns to me over and over as a metaphor for ourselves.

Marriage is an ongoing, centuries-long social experiment that is mostly controlled by the individuals in the relationships who insist on determining what the relationship terms are going to be. And that's why the terms of marriage change with every century and decade. We're shaping it from the inside. Marriage endures because it evolves. Obviously it does. None of us would accept marriage on its 13th century terms, not even the most conservative people...

The great Sufi poet and philosopher Rumi once advised his students to write down the three things they most wanted in life. If any item on the list clashes with any other item, Rumi warned, you are destined for unhappiness. Better to live a life of single-pointed focus, he taught. But what about the benefits of living harmoniously among extremes? What if you could somehow create an expansive enough life that you could synchronize seemingly incongruous opposites into a worldview that excludes nothing?

The best way is to read it all every day from the start, correcting as you go along, then go on from where you stopped the day before. When it gets so long that you can't do this every day read back two or three chapters each day; then each week read it all from the start. That's how you make it all of one piece.

The presence of industrial quantities of Byzantine pottery dating from the sixth century AD on the headland at Tintagel, Chinese silk in the tombs around Mecca and 'Arabic' numerals in the 13th-century beams of Salisbury Cathedral tell us we have been interdependent not for decades but across millennia.