A Quote by Mason Cooley

To understand a literary style, consider what it omits.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

Every genuinely literary style, from the high authorial voice to Foster Wallace and his footnotes-within-footnotes, requires the reader to see the world from somewhere in particular, or from many places. So every novelist's literary style is nothing less than an ethical strategy - it's always an attempt to get the reader to care about people who are not the same as he or she is.

There are so many new young poets, novelists, and playwrights who are much less politically committed than the former generations. The trend is to be totally concentrated on the literary aesthetic and to consider politics to be something dirty that shouldn't be mixed with an artistic or a literary vocation.

I intend Deaths in Venice to contribute both to literary criticism and to philosophy. But it's not "strict philosophy" in the sense of arguing for specific theses. As I remark, there's a style of philosophy - present in writers from Plato to Rawls - that invites readers to consider a certain class of phenomena in a new way. In the book, I associate this, in particular, with my good friend, the eminent philosopher of science, Nancy Cartwright, who practices it extremely skilfully.

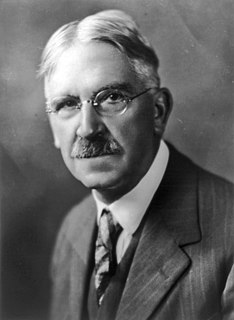

When we consider the close connection between science and industrial development on the one hand, and between literary and aesthetic cultivation and an aristocratic social organization on the other, we get light on the opposition between technical scientific studies and refining literary studies. We have before us the need of overcoming this separation in education if society is to be truly democratic.

I changed my writing style deliberately. My first two novels were written in a very self-consciously literary way. After I embraced gay subject matter, which was then new, I didn't want to stand in its way. I wanted to make the style as transparent as possible so I could get on with it and tell the story, which was inherently interesting.