A Quote by Massimo Pigliucci

If a theory purports to explain everything, then it is likely not explaining much at all.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

[T]he theory of output as a whole, which is what the following book purports to provide, is much more easily adapted to the conditions of a totalitarian state, than is the theory of production and distribution of a given output produced under the conditions of free competition and a large measure of laissez-faire.

What would it mean if there were a theory that explained everything? And just what does "everything" actually mean, anyway? Would this new theory in physics explain, say the meaning of human poetry? Or how economics work? Or the stages of psychosexual development? Can this new physics explain the currents of ecosystems, or the dynamics of history, or why human wars are so terribly common?

For if as scientists we seek simplicity, then obviously we try the simplest surviving theory first, and retreat from it only when it proves false. Not this course, but any other, requires explanation. If you want to go somewhere quickly, and several alternate routes are equally likely to be open, no one asks why you take the shortest. The simplest theory is to be chosen not because it is the most likely to be true but because it is scientifically the most rewarding among equally likely alternatives. We aim at simplicity and hope for truth.

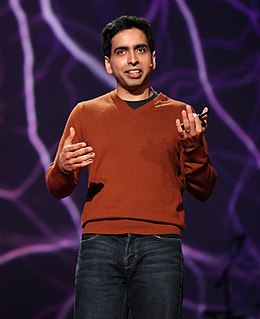

A good traditional conceptual instruction is what I got from my better professors at MIT. They would be at a chalkboard, and they would literally be explaining something and working through a problem, but it wasn't rote. They were explaining the underlying theory and processes and intuition behind it.

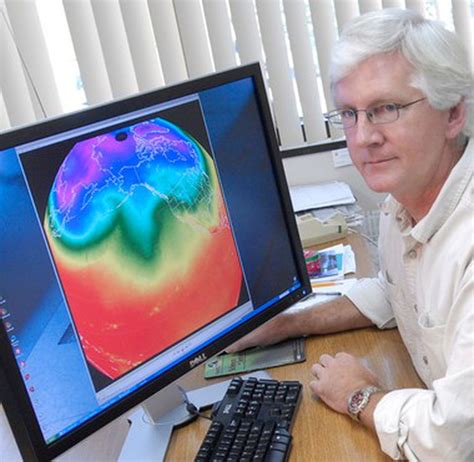

Time, among all concepts in the world of physics, puts up the greatest resistance to being dethroned from ideal continuum to the world of the discrete, of information, of bits.... Of all obstacles to a thoroughly penetrating account of existence, none looms up more dismayingly than 'time.' Explain time? Not without explaining existence. Explain existence? Not without explaining time. To uncover the deep and hidden connection between time and existence ... is a task for the future.

Catastrophe Theory is-quite likely-the first coherent attempt (since Aristotelian logic) to give a theory on analogy. When narrow-minded scientists object to Catastrophe Theory that it gives no more than analogies, or metaphors, they do not realise that they are stating the proper aim of Catastrophe Theory, which is to classify all possible types of analogous situations.