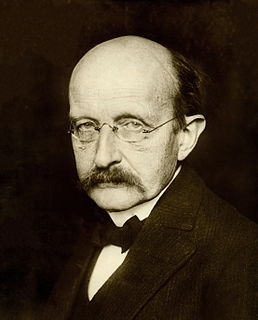

A Quote by Max Planck

Scientific discovery and scientific knowledge have been achieved only by those who have gone in pursuit of it without any practical purpose whatsoever in view.

Related Quotes

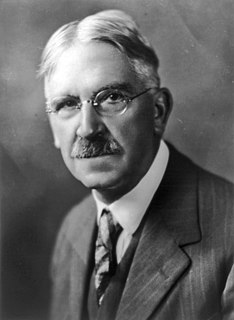

The routine of custom tends to deaden even scientific inquiry; it stands in the way of discovery and of the active scientific worker. For discovery and inquiry are synonymous as an occupation. Science is a pursuit, not a coming into possession of the immutable; new theories as points of view are more prized than discoveries that quantitatively increase the store on hand.

What struck me most in England was the perception that only those works which have a practical tendency awake attention and command respect, while the purely scientific, which possess far greater merit are almost unknown. And yet the latter are the proper source from which the others flow. Practice alone can never lead to the discovery of a truth or a principle. In Germany it is quite the contrary. Here in the eyes of scientific men no value, or at least but a trifling one, is placed upon the practical results. The enrichment of science is alone considered worthy attention.

The responsibility for the creation of new scientific knowledge - and for most of its application - rests on that small body of men and women who understand the fundamental laws of nature and are skilled in the techniques of scientific research. We shall have rapid or slow advance on any scientific frontier depending on the number of highly qualified and trained scientists exploring it.

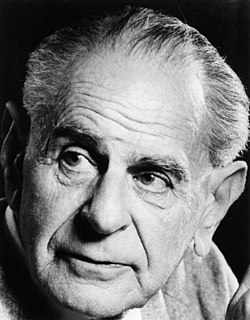

The fact that these scientific theories have a fine track record of successful prediction and explanation speaks for itself. (Which is not to say that I don't directly discuss the work of those philosophers who would disagree.) But even if we grant this, many will argue that scientific knowledge in humans, and, indeed, reflective knowledge in general, is quite different in kind from the knowledge we see in other animals.

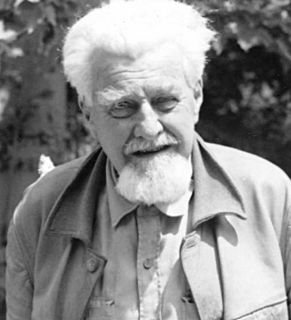

It is high time that laymen abandoned the misleading belief that scientific enquiry is a cold dispassionate enterprise, bleached of imaginative qualities, and that a scientist is a man who turns the handle of discovery; for at every level of endeavour scientific research is a passionate undertaking and the Promotion of Natural Knowledge depends above all on a sortee into what can be imagined but is not yet known.