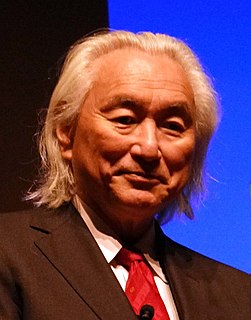

A Quote by Michael Shermer

Skeptics question the validity of a particular claim by calling for evidence to prove or disprove it.

Related Quotes

If one were to claim that the U.S. occupation forces in Iraq have been provided with "keys to heaven" by the Pentagon, would that need historical research to be disproved or would you just say, "That's just propaganda"? Indeed, how can you disprove the claim that U.S. soldiers have such keys? Or why should you disprove such ridiculous claims? It is the accusers who must provide the evidence.

When you look at the calculation, it's amazing that every time you try to prove or disprove time travel, you've pushed Einstein's theory to the very limits where quantum effects must dominate. That's telling us that you really need a theory of everything to resolve this question. And the only candidate is string theory.

Incidentally, when we're faced with a "prove or disprove," we're usually better off trying first to disprove with a counterexample, for two reasons: A disproof is potentially easier (we need just one counterexample); and nitpicking arouses our creative juices. Even if the given assertion is true, our search for a counterexample often leads to a proof, as soon as we see why a counterexample is impossible. Besides, it's healthy to be skeptical.

If all the evidence is weighed carefully and fairly, it is indeed justifiable, according to the canons of historical research, to conclude that the sepulcher of Joseph of Arimathea, in which Jesus was buried, was actually empty on the morning of the first Easter. And no shred of evidence has yet been discovered in literary sources, epigraphy, or archaeology that would disprove this statement.

When you ask why did some particular question occur to a scientist or philosopher for the first time, or why did this particular approach seem natural, then your questions concern the context of discovery. When you ask whether the argument the philosopher puts forth to answer that question is sound, or whether the evidence justifies the scientific theory proposed, then you've entered the context of justification. Considerations of history, sociology, anthropology, and psychology are relevant to the context of discovery, but not to justification.