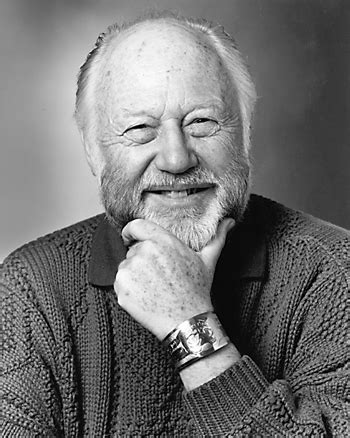

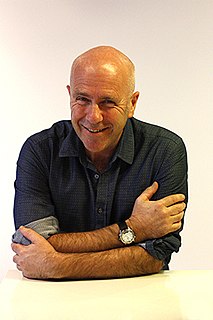

A Quote by Michael Smith

I was not proficient in Latin and so was not able to go to Oxford or Cambridge. However, I did enter the first-rate chemistry honours program at the University of Manchester in 1950, where the professors were E.R.H. Jones and M.G. Evans, and graduated in 1953, with the financial support of a Blackpool Education Committee Scholarship.

Related Quotes

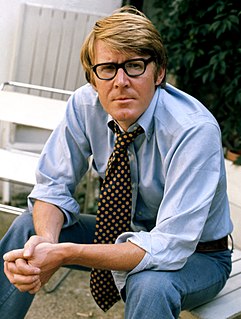

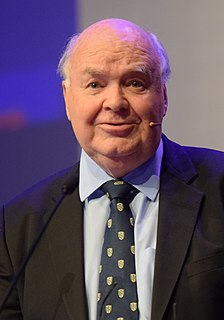

My experience came before most of you were born. My school was a state school in Leeds and the headmaster usually sent students to Leeds University but he didn't normally send them to Oxford or Cambridge. But the headmaster happened to have been to Cambridge and decided to try and push some of us towards Oxford and Cambridge. So, half a dozen of us tried - not all of us in history - and we all eventually got in. So, to that extent, it [The History Boys] comes out of my own experience.

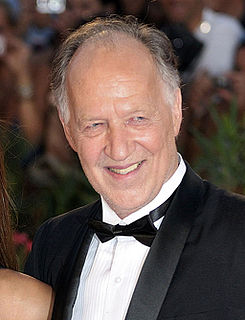

I was good at math and science, and it was expected that I would attend the University of Washington in Seattle and become an engineer. But by the time I was seventeen, I was ready to leave home, a decision my parents agreed to support if I could obtain a scholarship. MIT did not grant me one, but the University of Chicago did.

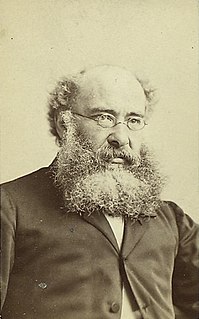

From age 16 on, I found school boring and failed A-level Physics at my first attempt. This was necessary for university entrance, and so I stayed an extra year to repeat it. This time, I did splendidly and was admitted to Sheffield University, my first choice because of their excellent Chemistry Department.