A Quote by Michael Wolff

Rusbridger had risen at the Guardian through the years when it not only had the support and fail-safe mechanism of the Scott Trust, but guaranteed operating income from public-service advertising. Nobody had to sell anything.

Related Quotes

During the fiscal year ending in 1861, expenses of the federal government had been $67 million. After the first year of armed conflict they were $475 million and, by 1865, had risen to one billion, three-hundred million dollars. On the income side of the ledger, taxes covered only about eleven per cent of that figure. By the end of the war, the deficit had risen to $2.61 billion. That money had to come from somewhere.

Look, I think that when we started Virgin Atlantic 30 years ago, we had one 747 competing with the airlines that had an average of 300 planes each. Every single one of those have gone bankrupt because they didn't have customer service. They had might, but they didn't have customer service, so customer service is everything in the end.

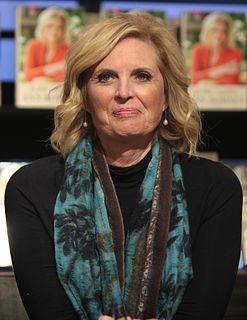

They were not easy years. You have to understand, I was raised in a lovely neighborhood, as was Mitt, and at BYU, we moved into a $62-a-month basement apartment with a cement floor and lived there two years as students with no income... Neither one of us had a job, because Mitt had enough of an investment from stock that we could sell off a little at a time.

People had been working for so many years to make the world a safe, organized place. Nobody realized how boring it would become. With the whole world property-lined and speed-limited and zoned and taxed and regulated, with everyone tested and registered and adressed and recorded. Nobody had left much room for adventure, except maybe the kind you could buy. [...] The laws that keep us safe, these same laws condemn us to boredom.

So fully am I impressed with the vast importance and necessity of attaining what will be the object of my motion this night, that if, during the almost forty years that I have had the honour of a seat in parliament, I had been so fortunate as to accomplish that, and that only, I should think I had done enough, and could retire from public life with comfort, and the conscious satisfaction, that I had done my duty.

The great philosophers of the past who wrote so beautifully - Rousseau, John Stuart Mill - had to write beautifully because they had to sell their work to journals. They had to sell books to the general public because they could not hold positions in universities. Mill was an atheist, and, therefore, could not hold a position in a university.