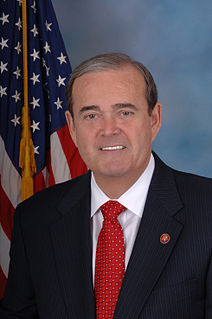

A Quote by Mike Quigley

I taught policy and politics for seven years at a university. I told my students lobbyists are not a bad thing; they're absolutely vital.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

I think about my education sometimes. I went to the University of Chicago for awhile after the Second World War. I was a student in the Department of Anthropology. At that time they were teaching that there was absolutely no difference between anybody. They may be teaching that still. Another thing they taught was that no one was ridiculous or bad or disgusting. Shortly before my father died, he said to me, ‘You know – you never wrote a story with a villain in it.’ I told him that was one of the things I learned in college after the war.

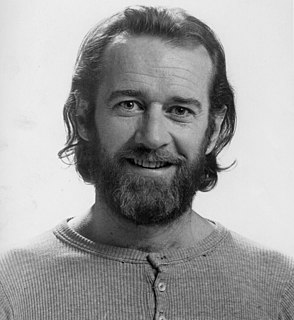

There are some people that aren't into all the words. There are some people who would have you not use certain words. Yeah, there are 400,000 words in the English language, and there are seven of them that you can't say on television. What a ratio that is. 399,993 to seven. They must really be bad. They'd have to be outrageous, to be separated from a group that large. All of you over here, you seven. Bad words. That's what they told us they were, remember? 'That's a bad word.' You know bad words. Bad thoughts. Bad intentions.

I've known for years that the university underserved the community, because we assumed that university education is for 18- to 22-year-olds, which is a proposition that's so absurd it is absolutely mind-boggling that anyone ever conceptualized it. Why wouldn't you take university courses throughout your entire life?

More than half of my former students teach - elementary and high school, community college and university. I taught them to be passionate about literature and writing, and to attempt to translate that passion to their own students. They are rookie teachers, most likely to be laid off and not rehired, even though they are passionate.

My analysis is that most faith based systems depend upon an absolute moral order. The declaration of things as absolutely evil or absolutely good, as sin or virtue, puts liberalism into a horrible position because it's founded on no judgment on anything. As a result, any faith that is seriously practiced or understood is a challenge to the politics that depend on constituencies that would rather not be told that their choices are bad and their lives are not virtuous.

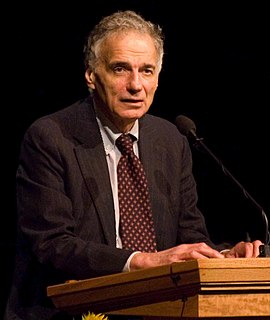

I fear that the impact of university censorship and university denial of due process will be to mis-educate a generation of students away from core values of civil liberties and constitutional safeguards. Students who have been led to believe by university administrators and faculty that censorship and denial of due process are acceptable norms will be more susceptible to accepting those norms in their post-university lives. That would be a tragedy for America.