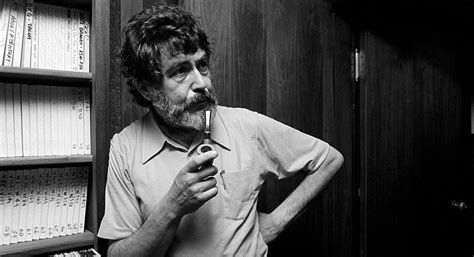

A Quote by Nat Hentoff

[Arthur Koestler] wrote some other very interesting books, but that book - I mean, if I were teaching, I don't care what the course is, I would say you really have to read "Darkness at Noon".

Related Quotes

The book that really, really shaped my politics and has forever is Arthur Koestler's "Darkness at Noon," which is a novel based on terrible fact about what it was like in Russia during Stalin's time when people actually believed that to get to the point where the Proletariat would triumph, anything that was necessary to be done should be done; the means didn't count.

I was less angry at [Carl] Armstrong, though I was angry at the people who came to his trial: Dan Ellsberg, who ordinarily I respected a lot; Philip Berrigan; the guy who teaches at Princeton still - I can't remember his name. And they were saying - well, they were saying, really, what Arthur Koestler had people saying on "Darkness at Noon." The means were unfortunate and, sadly, someone died, but the end is what is important and this was a great symbolic - something or other - sign against the war in Vietnam.

I think the books are the books. They were conceived as books. They weren't conceived as movies. When I write scripts, that's an idea and a situation that I think is a really good idea for a movie. When I'm writing a book, I'm not thinking, "Oh, this would be a great movie." This would be a very interesting book. And I think the books are things that cannot really be adapted into another medium.

Heidegger wrote a book called Was Ist Das Ding - What Is a Thing? which was kind of interesting and influential to me, as a matter of fact. It's a small paperback, which I read. It's about the nature of thingness; what is it? It's a very penetrating analysis of that, and I think a rather influential book. I know other artists who have read it and come up with it.

One of the things I do take some pride in is that if you had never read an article about my life, if you knew nothing about me, except that my books were being set in front of you to read, and if you were to read those books in sequence, I don't think you would say to yourself, 'Oh my God, something terrible happened to this writer in 1989.'

Throughout his last half-dozen books, for example, Arthur Koestler has been conducting a campaign against his own misunderstanding of Darwinism. He hopes to find some ordering force, constraining evolution to certain directions and overriding the influence of natural selection. [...] Darwinism is not the theory of capricious change that Koestler imagines. Random variation may be the raw material of change, but natural selection builds good design by rejecting most variants while accepting and accumulating the few that improve adaptation to local environments.

I have often wondered how anyone who does not read, by which I mean daily, having some book going all the time, can make it through life. Indeed if I were required to make a sharp division in the very nature of people, I would be tempted to make it there: readers and nonreaders of books... It is astonishing how the presence or absence of this habit so consistently characterizes an individual in other respects; it is as though it were a kind of barometer of temperament, of personality, even of character. Aside from that, for me it constituted something like sanity insurance.

In my early teens, I read every bound volume of the magazine Punch. Every writer of any distinction in the English language, and I mean including America and England, at some time wrote for Punch. Jerome K. Jerome, who wrote Three Men In A Boat, I loved. I was very impressed when I read a piece by Mark Twain in Punch, and realized that despite the fact that they were on different continents, Jerome K. Jerome and Mark Twain had the same kind of laconic, laid-back, "The human race is damn stupid, but quite interesting" attitude. They were almost talking with the same voice.