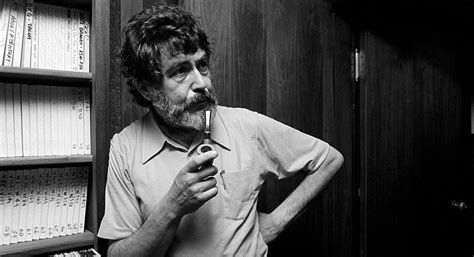

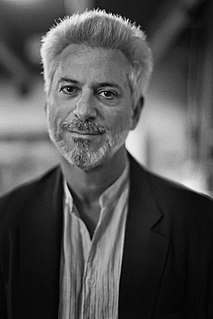

A Quote by Nat Hentoff

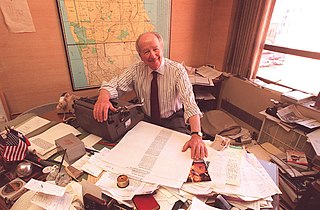

I write a syndicated column for The Washington Post that goes to about 200, 250 papers.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

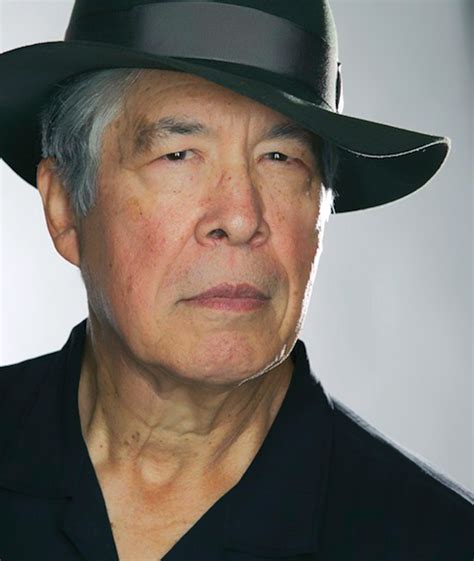

I had written a lot about my dog dying before. I wrote a newspaper column about it and it turned out to be the most popular column I'd ever written. That and the lame Joni Mitchell column I did. But the dog column, my god! People love dogs. Anybody who writes regularly should know, when in doubt: dogs! If you're a columnist, when in doubt, write a column about the culture of narcissism - like a scolding column about the culture of narcissism - or write something about dogs. That's the homerun in my take.

I would say that the Pentagon Papers case of 1971 - in which the government tried to block the 'The New York Times' and 'The Washington Post' and other newspapers from publishing papers that they obtained from a secret study of how we got involved in the war in Vietnam - that is probably the most important case.

I knew I had found my life's passion after writing my first column for The Washington Post. The response was like nothing we had seen in the business section. Everyday people were writing that finally someone was speaking to them in a way that was understandable. I think we were all shocked at how many readers wrote in to say that they too had a Big Mama who taught them about money.