A Quote by Nina Easton

We know that inflation distorts economic behavior. In the 1970s, a combination of high tax rates and inflation prompted investors to flee production in favor of protection.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

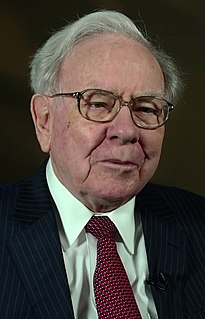

It makes no difference to a widow with her savings in a 5 percent passbook account whether she pays 100 percent income tax on her interest income during a period of zero inflation or pays no income tax during years of 5 percent inflation. Either way, she is 'taxed' in a manner that leaves her no real income whatsoever. Any money she spends comes right out of capital. She would find outrageous a 100 percent income tax but doesn't seem to notice that 5 percent inflation is the economic equivalent.

[Australian Reserve Bank] Governor MacFarlane said recently when Paul Volcker broke the back of American inflation it's regarded as the policy triumph of the Western world. When I broke the back of Australian inflation they say, "Oh, you're the fellow that put the interest rates up." Am I not the same fellow that gave them the 15 years of good growth and high wealth that came from it?