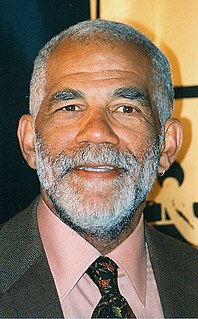

A Quote by Noam Chomsky

The atrocities in Cambodia are a direct and understandable response to the violence of the imperial system.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

When you vaccinate someone, or when you get infected, the microbe is presenting itself to the immune system in a way that the immune system recognizes the important elements of the microbe and makes an immune response, both an antibody response and a cellular response, to ultimately contain the microbe.

My approach to violence is that if it's pertinent, if that's the kind of movie you're making, then it has a purposeI think there's a natural system in your own head about how much violence the scene warrants. It's not an intellectual process, it's an instinctive process. I like to think it's not violence for the sake of violence and in this particular film, it's actually violence for the annihilation of violence.

Most people assume that physician language is akin to technical, non-understandable jargon. It does not have to be that way. Doctors do not perform witchcraft. They simply interpret what they are told and what tests reveal. They diagnose and prescribe treatment. Our responsibility is to help doctors know what is going on in our bodies and to insist on clear, precise, understandable language in response.

Boxes and rectangles on the side or top of a website simply do not deliver against brand advertising goals. Like it or not, boxes and rectangles have for the most part become the province of direct response advertising, or brand advertising that pays, on average, as if it's driven by direct response metrics.

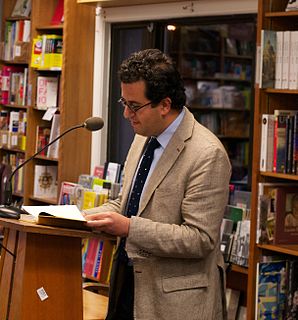

One of the unspoken themes that I'm grappling with in Day of Honey is the relationship between violence and cosmopolitanism. It's one thing to comprehend violence as an outgrowth of ignorance, poverty, and backwardness. It's another matter entirely to confront incredible atrocities in a country with a rich civic and intellectual life.

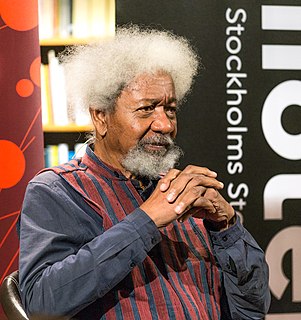

I think we can see violence in a whole range of realms. We certainly see it in the media, where extreme violence is now so pervasive that people barely blink when they see it, and certainly raise very few questions about what it means pedagogically and politically. Violence is the DNA, the nervous system of this system's body politic.