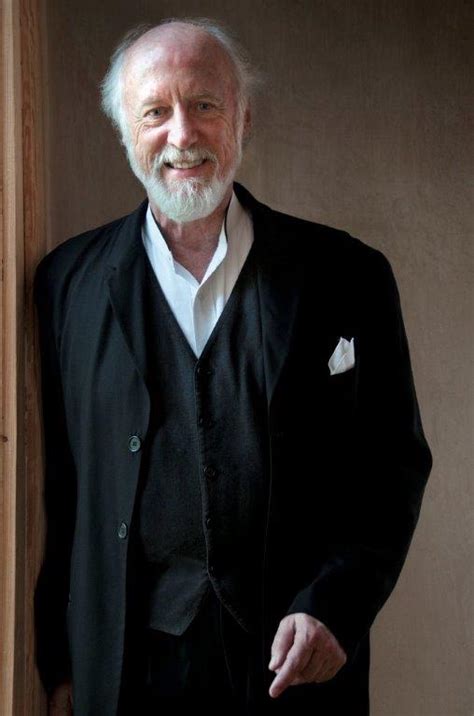

A Quote by Noam Chomsky

That intellectuals, including academics, would become a "new class" of technocrats, claiming the name of science while cooperating with the powerful, was predicted by [Mikhail] Bakunin in the early days of the formation of the modern intelligentsia in the 19th century.

Related Quotes

[Mikhail Bakunin] expectations were generally confirmed, including his prediction that some would seek to gain state power on the backs of popular revolution, then constructing a "Red bureaucracy" that would be one of the worst tyrannies in history, while others would recognize that power lies elsewhere and would serve as its apologists, becoming mystifies, "disablers," and managers while demanding the right to function in "technocratic isolation," in World Bank lingo.

While Pickstown may not be what it once was, it still is framed by the natural beauty of the ancient river, the sweep of the Great Plains, and the long, unbroken shoreline of the lake behind the dam. It gave me a 19th-century childhood in a modern mid-20th-century town, and for that I will always be grateful.

I was really interested in 20th century communalism and alternative communities, the boom of communes in the 60s and 70s. That led me back to the 19th century. I was shocked to find what I would describe as far more utopian ideas in the 19th century than in the 20th century. Not only were the ideas so extreme, but surprising people were adopting them.

People have asked me about the 19th century and how I knew so much about it. And the fact is I really grew up in the 19th century, because North Carolina in the 1950s, the early years of my childhood, was exactly synchronous with North Carolina in the 1850s. And I used every scrap of knowledge that I had.

Western intellectuals, and also Third World intellectuals, were attracted to the Bolshevik counter-revolution because Leninism is, after all, a doctrine which says that the radical intelligentsia have a right to take state power and to run their countries by force, and that is an idea which is rather appealing to intellectuals.

In the early 19th century, when the country was transitioning from an agrarian to an industrial economy, we subsidised transportation and created a national bank. In the post-WWII era, we as a federal government made strategic investments in emerging technologies including microelectronics, telecommunications and biotechnology.

The 19th century Mormons, including some of my ancestors, were not eager to practice plural marriage. They followed the example of Brigham Young, who expressed his profound negative feelings when he first had this principle revealed to him. The Mormons of the 19th century who practiced plural marriage, male and female, did so because they felt it was a duty put upon them by God.

Though now we think of fairy tales as stories intended for very young children, this is a relatively modern idea. In the oral tradition, magical stories were enjoyed by listeners young and old alike, while literary fairy tales (including most of the tales that are best known today) were published primarily for adult readers until the 19th century.