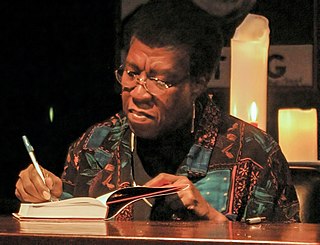

A Quote by Octavia E. Butler

I was attracted to science fiction because it was so wide open. I was able to do anything and there were no walls to hem you in and there was no human condition that you were stopped from examining.

Related Quotes

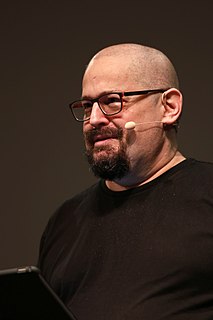

Science fiction is fantasy about issues of science. Science fiction is a subset of fantasy. Fantasy predated it by several millennia. The '30s to the '50s were the golden age of science fiction - this was because, to a large degree, it was at this point that technology and science had exposed its potential without revealing the limitations.

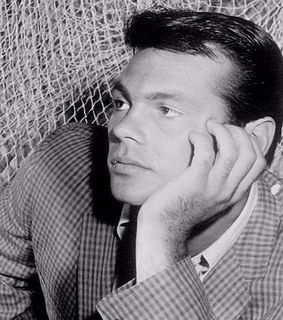

Can any rational person believe that the Bible is anything but a human document? We now know pretty well where the various books came from, and about when they were written. We know that they were written by human beings who had no knowledge of science, little knowledge of life, and were influenced by the barbarous morality of primitive times, and were grossly ignorant of most things that men know today.

Science fiction is a weird category, because it's the only area of fiction I can think of where the story is not of primary importance. Science fiction tends to be more about the science, or the invention of the fantasy world, or the political allegory. When I left science fiction, I said "They're more interested in planets, and I'm interested in people."

Ernest once told me that the word paradise was a Persian words that meant walled garden. I knew then that he understood how necessary the promises we made to each other were to our happiness. You couldn't have real freedom unless you knew were the walls were and tended to them. We could lean on the walls because they existed; they existed because we leaned on them.

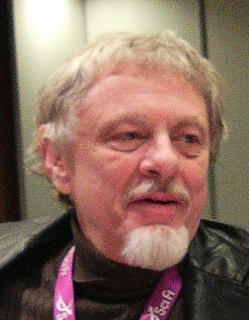

The films that I loved growing up were the science fiction films from the late seventies and early eighties [films], which were more about the people and how they are affected by the environments that they are in. Whether they are sort of futuristic or alien of whatever they are; that was the science fiction that I loved. So that is what we tried to make, the sort of film that felt like those old films.

People knew there were two ways of coming at truth. One was science, or what the Greeks called Logos, reason, logic. And that was essential that the discourse of science or logic related directed to the external world. The other was mythos, what the Greeks called myth, which didn't mean a fantasy story, but it was a narrative associated with ritual and ethical practice but it helped us to address problems for which there were no easy answers, like mortality, cruelty, the sorrow that overtakes us all that's part of the human condition. And these two were not in opposition, we needed both.