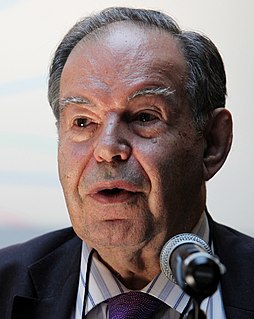

A Quote by Ornette Coleman

I have often read critical pieces where the critic said that what the composer was trying to do didn't come off. I have wondered what the critic meant if he didn't know what the composer was trying to do.

Related Quotes

Paradoxically, the simpler poetry is, the more difficult it becomes for a critic to discuss intelligently. Trained to explicate, the critic often loses the ability to evaluate literature outside the critical act. A work is good only in proportion to the richness and complexity of interpretations it provokes.

Critical thinking does seem a superior sort of thinking because it seems as though the critic is actually going beyond the scope of what is being criticized in order to criticize it. That is only rarely a true assumption because, most often, the critic will seize on some little aspect that he or she understands and tackle only that.

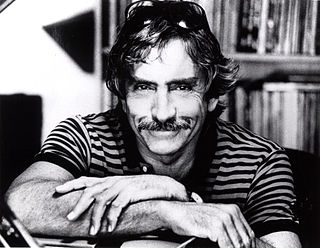

You find very few critics who approach their job with a combination of information and enthusiasm and humility that makes for a good critic. But there is nothing wrong with critics as long as people don't pay any attention to them. I mean, nobody wants to put them out of a job and a good critic is not necessarily a dead critic. It's just that people take what a critic says as a fact rather than an opinion, and you have to know whether the opinion of the critic is informed or uninformed, intelligent of stupid -- but most people don't take the trouble.

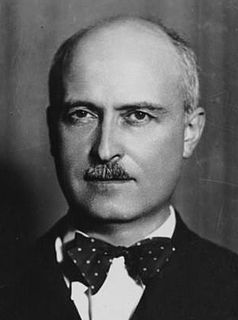

I was the first critic ever to win a Tony - for co-authoring 'Elaine Stritch at Liberty.' Criticism is a life without risk; the critic is risking his opinion, the maker is risking his life. It's a humbling thought but important for the critic to keep it in mind - a thought he can only know if he's made something himself.