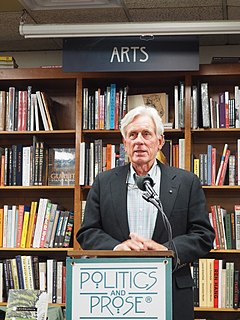

A Quote by P. J. O'Rourke

When you're a war correspondent, the reader is for you because the reader is saying, 'Gee, I wouldn't want to be doing that.' They're on your side.

Related Quotes

For me, one of the reasons I love this form - the personal essay form - is because it's a way of forming an intimacy with the reader. What I'm saying to the reader is: I'm going to tell you something; I'm going to be generous; I'm going to offer. The confession, on the other hand, is sort of an imposition because you're asking the reader to forgive you or somehow exonerate you or say, "Hey, I'm even worse." But what I'm interested in doing is being generous and offering a perspective or suggesting a way of thinking about something.

In my couple of books, including Going Clear, the book about Scientology, I thought it seemed appropriate at the end of the book to help the reader frame things. Because we've gone through the history, and there's likely conflictual feelings in the reader's mind. The reader may not agree with me, but I don't try to influence the reader's judgment. I know everybody who picks this book up already has a decided opinion. But my goal is to open the reader's mind a little bit to alternative narratives.

With a 660-page book, you don't read every sentence aloud. I am terrified for the poor guy doing the audio book. But I do because I think we hear them aloud even if it's not an audio book. The other goofy thing I do is I examine the shape of the words but not the words themselves. Then I ask myself, "Does it look like what it is?" If it's a sequence where I want to grab the reader and not let the reader go then it needs to look dense. But at times I want the reader to focus on a certain word or a certain image and pause there.

The first rule is you have to create a reality that makes the reader want to come back and see what happens next. The way I tried to do it, I'd create characters that the reader could instantly recognize, and hopefully bond with, and put them through situations that keep the reader on the edge of their seat.

We must be forewarned that only rarely does a text easily lend itself to the reader's curiosity... the reading of a text is a transaction between the reader and the text, which mediates the encounter between the reader and writer. It is a composition between the reader and the writer in which the reader "rewrites" the text making a determined effort not to betray the author's spirit.