A Quote by Paul Rotha

A film in which the speech and sound effects are perfectly synchronized and coincide with their visual image on the screen is absolutely contrary to the aims of cinema. It is a degenerate and misguided attempt to destroy the real use of the film and cannot be accepted as coming within the true boundaries of the cinema.

Related Quotes

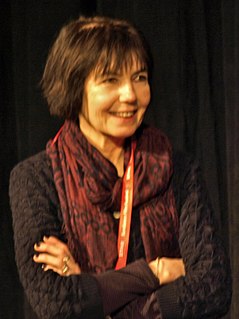

To me, a revolutionary film is not a film about a revolution. It has a lot more to do with the art form. It's a film that is revolting against the old established language of cinema that had been brainwashing the people for decades. It is a film that is trying to find ways to use sound and image differently.

The structure of my novels has nothing to do with the narrative mode of cinema. My novels would be very difficult to film without ruining them completely. I think this is the area where writers need to place ourselves: from a position of absolute modernity and contemporaneity, creating a culture of objects which cinema cannot.

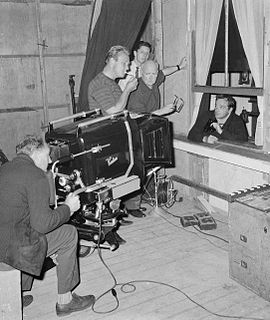

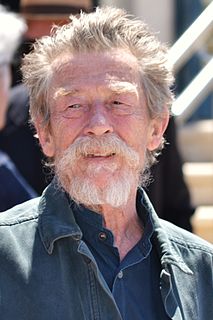

The director [Elfar Adalsteins] came to me through my agent and I had a read of the script [of the "Sailcloth]. I thought immediately this is someone who is writing for the cinema. Not having to go through the tedious business of taking something from literature and making that awful leap that is so difficult to make anyway, from literature to cinema. It's refreshing to be able to deal with a subject like that, to be written where the driving force is the image on screen and you don't need any words. The more that we can do that [in film], the better.