A Quote by Percy Bysshe Shelley

It is vain philosophy that supposes more causes than are exactly adequate to explain the phenomena of things.

Related Quotes

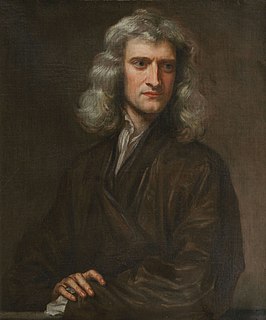

Our design, not respecting arts, but philosophy, and our subject, not manual, but natural powers, we consider chiefly those things which relate to gravity, levity, elastic force, the resistance of fluids, and the like forces, whether attractive or impulsive; and therefore we offer this work as mathematical principles of philosophy; for all the difficulty of philosophy seems to consist in this from the phenomena of motions to investigate the forces of nature, and then from these forces to demonstrate the other phenomena.

There cannot be a language more universal and more simple, more free from errors and obscurities...more worthy to express the invariable relations of all natural things [than mathematics]. [It interprets] all phenomena by the same language, as if to attest the unity and simplicity of the plan of the universe, and to make still more evident that unchangeable order which presides over all natural causes

In the final, the positive, state, the mind has given over the vain search after absolute notions, the origin and destination of the universe, and the causes of phenomena, and applies itself to the study of their laws - that is, their invariable relations of succession and resemblance. Reasoning and observation, duly combined, are the means of this knowledge. What is now understood when we speak of an explanation of facts is simply the establishment of a connection between single phenomena and some general facts.

The hypotheses which we accept ought to explain phenomena which we have observed. But they ought to do more than this; our hypotheses ought to foretell phenomena which have not yet been observed; ... because if the rule prevails, it includes all cases; and will determine them all, if we can only calculate its real consequences. Hence it will predict the results of new combinations, as well as explain the appearances which have occurred in old ones. And that it does this with certainty and correctness, is one mode in which the hypothesis is to be verified as right and useful.

I believe it to be of particular importance that the scientist have an articulate and adequate social philosophy, even more important than the average man should have a philosophy. For there are certain aspects of the relation between science and society that the scientist can appreciate better than anyone else, and if he does not insist on this significance no one else will, with the result that the relation of science to society will become warped, to the detriment of everybody.

As a man of pleasure, by a vain attempt to be more happy than any man can be, is often more miserable than most men are, so the sceptic, in a vain attempt to be wise beyond what is permitted to man, plunges into a darkness more deplorable, and a blindness more incurable than that of the common herd, whom he despises, and would fain instruct.