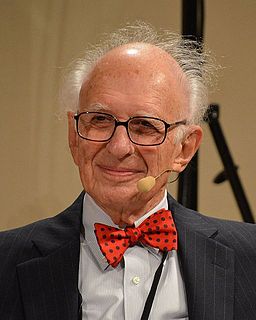

A Quote by Peter Agre

My goal was to develop into an independent research scientist studying clinical problems at the laboratory bench, but I felt that postgraduate residency training in internal medicine was necessary.

Related Quotes

Towards the end of the military service, I had to make what I assume has been the most important decision in my career: to start a residency in clinical medicine, in surgery, which was my favorite choice, or to enroll into graduate school and start a career in scientific research. It was clear to me that I was heading for graduate school.

I grew up in Muenchen where my father has been a professor for pharmaceutic chemistry at the university. He had studied chemistry and medicine, having been a research student in Leipzig with Wilhelm Ostwald, the Nobel Laureate 1909. So I became familiar with the life of a scientist in a chemical laboratory quite early.

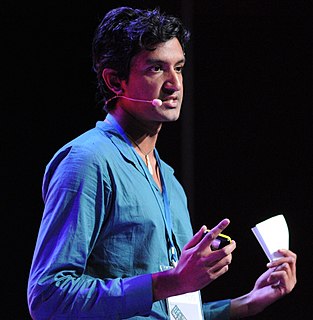

When I was in graduate school at MIT I was trying to think about how to develop software and systems for farmers and villagers in India. In the process of doing that, I realized that my reference point was internal to the laboratory, rather than in the communities that I was wanting to serve. I realized that I could no longer assume what a good technology looks like from inside the laboratory; instead, I had to be in the world with people. Not just designing for them but with them.

In 1998, I set up and directed a research group at the Nanotechnology Institute newly created in the Research Center of Karlsruhe. This allowed to offer to former post-doctoral coworkers the opportunity to develop and to progressively set up independent research activities in nanoscience and nanotechnology.

It is simply no longer possible to believe much of the clinical research that is published, or to rely on the judgment of trusted physicians or authoritative medical guidelines. I take no pleasure in this conclusion, which I reached slowly and reluctantly over my two decades as an editor of The New England Journal of Medicine.