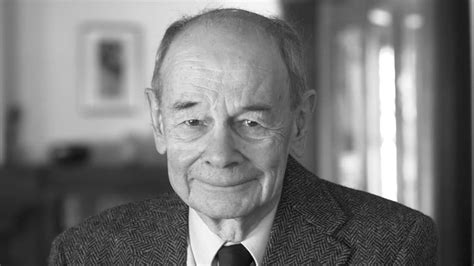

A Quote by Philip Jenkins

When the war started, religion and superstition (whatever the difference is) permeated the lives of ordinary soldiers, who lived in a thought world not too far removed from the seventeenth century.

Related Quotes

Although the United States lost a quarter of a million men and women, civilians and soldiers, in World War II, that's considerably less than the Russians lost in soldiers at the Battle of Stalingrad alone. It's important to convey to countries and to people and to generations who have no experience of the 20th century as it was lived in Europe just how catastrophic it was.

What would be the difference if we retreated and let the French and Germans make decisions for the world? We tried that twice in the last century. Isolationsim, refusing to accept our role in the world, and delaying our response to evildoers ultimately cost fifty-three million lives in World War 2 alone. The preemption policy of the Bush administration, taking the war to the enemy and exporting democracy and freedom, has liberated fifty million.

World War II revealed two of the enduring features of the Keynesian Revolution. One was the moral difference between spending for welfare and spending for war. During the Depression very modest outlays for the unemployed seemed socially debilitating, economically unsound. Now expenditures many times greater for weapons and soldiers were perfectly safe. It's a difference that still persists.

Modernism really started with people getting infatuated with the idea of "it's the twentieth century, is this suitable for the twentieth century." This happened before the First World War and it wasn't just the soldiers. You can see it happening if you read the Bloomsbury biographies. It was a reaction to a great extent against Victorianism. There was so much that was repressive and stuffy. Victorian buildings were associated with it, and they were regarded as very ugly. Even when they weren't ugly, people made them ugly. They were painted hideously.