A Quote by Philip Kitcher

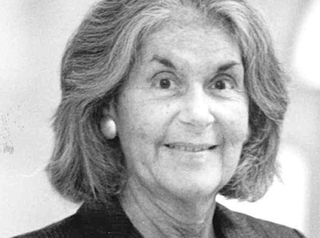

Sometime during the 1990s, when I was teaching philosophy at UCSD, my friend, colleague, and music teacher, Carol Plantamura, discussed the possibility of teaching a course together looking at ways in which various literary works (plays, stories, novels) had been treated as operas, and how different themes emerged in the opera and in its original. One of the pairings we planned to use was Mann's great novella and Britten's opera. Unfortunately, the course was never taught, but the idea remained with me.

Quote Topics

Been

Carol

Course

Different

Discussed

Emerged

Friend

Great

Had

How

Idea

Literary

Literary Works

Looking

Me

Music

Music Teacher

My Friend

Never

Novels

Opera

Original

Philosophy

Planned

Plays

Possibility

Remained

Sometime

Stories

Taught

Teacher

Teaching

Themes

Together

Treated

Unfortunately

Use

Various

Ways

Which

Works

Related Quotes

I was very young, maybe five. The opera was very... I was attracted to opera to the point that I think it's the reason I started to write music for films. I never studied. There are film and music school that teach you how to write music. I never studied that. But the influence of opera, which is a combination of storyline, visuals, staging, plus music... that was perhaps the best school I could have had. That's what gave me the idea of coming to Hollywood to write music for films.

I use biography, I use literary connections (as with Platen - this seems to me extremely helpful for appreciating the nuances of Mann's and Aschenbach's sexuality), I use philosophical sources (but not in the way many Mann critics do, where the philosophical theses and concepts seem to be counters to be pushed around rather than ideas to be probed), and I use juxtapositions with other literary works (including Mann's other fiction) and with works of music.

First, my frame of reference for the Britten opera shifted. I'd always thought of Britten's approach in Death in Venice as another exploration of the plight of the individual whose aspirations are at odds with those of the surrounding community: his last opera returning to the themes of Peter Grimes. As I read and listened and thought, however, Billy Budd came to seem a more appropriate foil for Death in Venice.

As I read Mann in German for the first time, the full achievement - both literary and philosophical - of Death in Venice struck me forcefully, so that, when I was invited to give the Schoff Lectures at Columbia, the opportunity to reflect on the contrasts between novella and opera seemed irresistible.

Opera was an enormous part of my childhood. My parents were both opera buffs, and they met in the box seat of an opera performance. And I also was a boy soprano, so before puberty hit, I was onstage playing a wide variety of orphans and urchins in all sorts of operas, and the sheer melodrama of their stories was just always appealing to me.

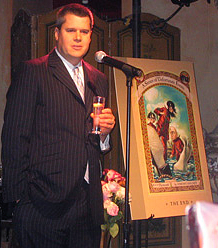

I've always loved opera; it never occurred to me that I would write a proper libretto. One of my closest friends is a composer, Paul Moravec, and a few years ago, Paul and I were at lunch, and I said to him, "you really have to write an opera." So, he says very casually to me, "I'll do it if you write the libretto." Well, little did I know that the within a couple of years we would end up getting a commission from the Santa Fe Opera to write an opera together, "The Letter," which turned out to be the most successful commissioned opera in the history of the Santa Fe Opera.

As any opera fan knows, lawyers and judges do not fare well in most operas. Just consider the productions of 'Andrea Chenier,' 'Aida, Norma,' 'Billy Budd,' 'Peter Grimes,' 'The Crucible,' 'Lost in the Stars,' 'The Marriage of Figaro,' 'The Makropulos Case' and Wagner's 'Ring' cycle. Around 1810, the theme of justice emerged in opera.

I've been a teacher all my life. I've had my own dance studio, my own acting studio for 18 years out here... I'm just a natural teacher. I teach on all my healing work now. I think actors teach any time they work anyway. We're teaching emotions, we're teaching how to deal with emotions, we're teaching how to get around issues and deal with them. Actors are some of the best teachers in the world, because they're teaching you through entertainment, and you don't know you're getting a message.

When I was young, I went to college, had a teacher who was, had been a student of Trilling's at Columbia, this was in California. And he, I started reading him around that time, and then I went to Columbia as well, Trilling was still teaching there, I took a course with him. He was not a great teacher, but he was, when I was younger, he was a good model for the kind of criticism I wanted to do, because he thought very dialectically.

I've been working with Riccardo Tisci from Givenchy.It's been a long collaboration, and I don't think it's going to stop now. It's very important to me. Riccardo is younger than me, so it's great to have someone new teaching you in everything, not just in fashion. I'm teaching him in French style, what a women's style is, but he's teaching me in all of these different styles of music.I love this new world for me. It's refreshing and nourishing to keep learning about new things.

The lights were off so that his heads could avoid looking at each other because neither of them was currently a particular engaging sight, nor had they been since he had made the error of looking into his soul. It had indeed been an error. It had been late one night-- of course. It had been a difficult day-- of course. There had been soulful music playing on the ship's sound system-- of course. And he had, of course, been slightly drunk. In other words, all the usual conditions that bring on a bout of soul searching had applied, but it had, nevertheless, clearly been an error.