A Quote by Prince

I like arguments.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

Most of this film, however, is about interpretation - are these people terrorists or freedom fighters? Are they good or bad? Is cutting timber good or bad? And I don't feel like the answers to those questions are simple, so we don't try to answer them for the audience. I wanted to elicit the strongest - and most heartfelt - arguments from the characters in the film and let those arguments bang up against the strongest arguments of their opponents.

I am well acquainted with all the arguments against freedom of thought and speech - the arguments which claim that it cannot exist, and the arguments which claim that it ought not to. I answer simply that they don't convince me and that our civilization over a period of four hundred years has been founded on the opposite notice.

Highly technical philosophical arguments of the sort many philosophers favor are absent here. That is because I have a prior problem to deal with. I have learned that arguments, no matter how watertight, often fall on deaf ears. I am myself the author of arguments that I consider rigorous and unanswerable but that are often not such much rebutted or even dismissed as simply ignored.

What do you know about me, given that I believe in secrecy? ... If I stick where I am, if I don't travel around, like anyone else I make my inner journeys that I can only measure by my emotions, and express very obliquely and circuitously in what I write. ... Arguments from one's own privileged experience are bad and reactionary arguments.

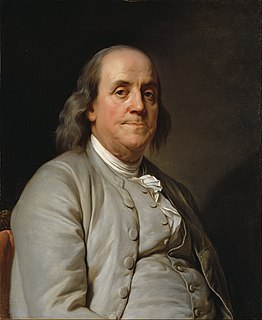

When confronted with two courses of action I jot down on a piece of paper all the arguments in favor of each one, then on the opposite side I write the arguments against each one. Then by weighing the arguments pro and con and cancelling them out, one against the other, I take the course indicated by what remains.

Satire works in a bunch of specific ways, like a very precisely-geared bomb. It's a bit like something that looks harmless, and you swallow it, but once it's inside you it's too late, and it triggers, blowing up. And it's your specific inner beliefs and faulty arguments that trigger a satire bomb. If your arguments work, the bomb doesn't trigger, it doesn't need to.