A Quote by Ralph Waldo Emerson

I know nothing which life has to offer so satisfying as the profound good understanding, which can subsist, after much exchange ofgood offices, between two virtuous men, each of whom is sure of himself, and sure of his friend. It is a happiness which postpones all other gratifications, and makes politics, and commerce, and churches, cheap.

Related Quotes

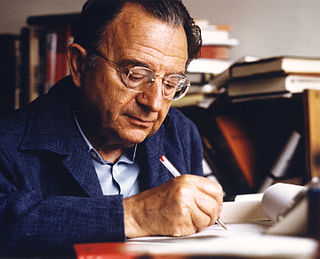

Modern man has transformed himself into a commodity; he experiences his life energy as an investment with which he should make the highest profit, considering his position and the situation on the personality market. He is alienated from himself, from his fellow men and from nature. His main aim is profitable exchange of his skills, knowledge, and of himself, his "personality package" with others who are equally intent on a fair and profitable exchange. Life has no goal except the one to move, no principle except the one of fair exchange, no satisfaction except the one to consume.p97.

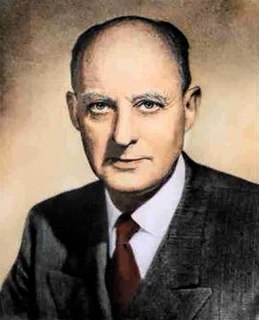

Nothing that is worth doing can be achieved in our lifetime; therefore we must be saved by hope. Nothing which is true or beautiful or good makes complete sense in any immediate context of history; therefore we must be saved by faith. Nothing we do, however virtuous, can be accomplished alone; therefore we must be saved by love. No virtuous act is quite as virtuous from the standpoint of our friend or foe as it is from our standpoint. Therefore we must be saved by the final form of love which is forgiveness.

When we see the many grave-stones which have fallen in, which have been defaced by the footsteps of the congregation, which lie buried under the ruins of the churches, that have themselves crumbled together over them; we may fancy the life after death to be as a second life, into which man enters in the figure, or the picture or the inscription, and lives longer there than when he was really alive. But this figure also, this second existence, dies out too, sooner or later. Time will not allow himself to be cheated of his rights with the monuments of men or with themselves.

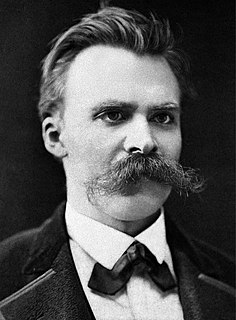

How much reverence has a noble man for his enemies!--and such reverence is a bridge to love.--For he desires his enemy for himself, as his mark of distinction; he can endure no other enemy than one in whom there is nothing to despise and very much to honor! In contrast to this, picture "the enemy" as the man of ressentiment conceives him--and here precisely is his deed, his creation: he has conceived "the evil enemy," "the Evil One," and this in fact is his basic concept, from which he then evolves, as an afterthought and pendant, a "good one"--himself!

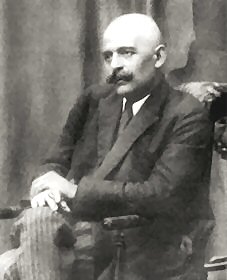

One of man's important mistakes, one which must be remembered, is his illusion in regard to his I. Man such as we know him, the 'man-machine,' the man who cannot 'do,' and with whom and through whom everything 'happens,' cannot have a permanent and single I. His I changes as quickly as his thoughts, feelings and moods, and he makes a profound mistake in considering himself always one and the same person; in reality he is always a different person, not the one he was a moment ago.

The happiness which God designs for His higher creatures is the happiness of being freely, voluntarily united to Him and to each other in an ecstasy of love and delight compared with which the most rapturous love between a man and a woman on this earth is mere milk and water. And for that they must be free.

Men are less hesitant about harming someone who makes himself loved than one who makes himself feared because love is held together by a chain of obligation which, since men are wretched creatures, is broken on every occasion in which their own interests are concerned; but fear is sustained by dread of punishment which will never abandon you.

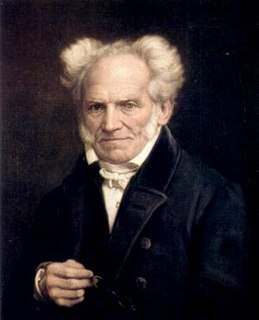

A man's knowledge may be said to be mature, in other words, when it has reached the most complete state of perfection to which he, as an individual, is capable of bringing it, when an exact correspondence is established between the whole of his abstract ideas and the things he has actually perceived for himself. His will mean that each of his abstract ideas rests, directly or indirectly, upon a basis of observation, which alone endows it with any real value; and also that he is able to place every observation he makes under the right abstract idea which belongs to it.

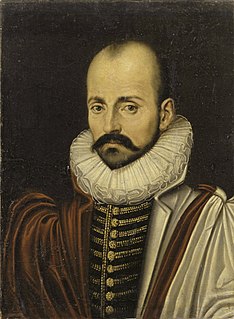

Business in a certain sort of men is a mark of understanding, and they are honored for it. Their souls seek repose in agitation, as children do by being rocked in a cradle. They may pronounce themselves as serviceable to their friends as troublesome to themselves. No one distributes his money to others, but every one therein distributes his time and his life. There is nothing of which we are so prodigal as of those two things, of which to be thrifty would be both commendable and useful.

But he found that a traveller's life is one that includes much pain amidst its enjoyments. His feelings are for ever on the stretch; and when he begins to sink into repose, he finds himself obliged to quit that on which he rests in pleasure for something new, which again engages his attention, and which also he forsakes for other novelties.