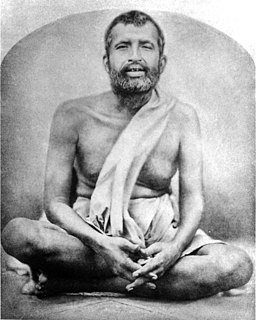

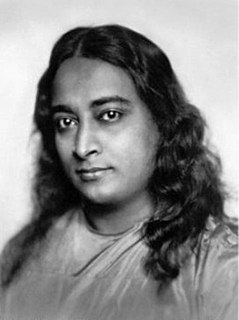

A Quote by Ramakrishna

The world is impermanent. One should constantly remember death.

Quote Topics

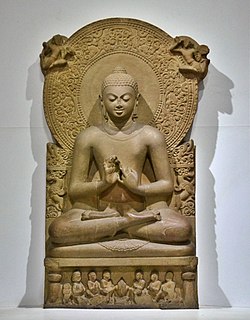

Related Quotes

We do not know whether it is good to live or to die. Therefore, we should not take delight in living, nor should we tremble at the thought of death. We should be equiminded towards death. This is the ideal. It may be long before we reach it, and only a few of us can attain it. Even then, we must keep it constantly in view, and the more difficult it seems of attainment, the greater should be the effort we put forth.

I love Death because he breaks the human pattern and frees us from pleasures too prolonged as well as from the pains of this world. It is pleasant, too, to remember that Death lies in our hands; he must come if we call him. ... I think if there were no death, life would be more than flesh and blood could bear.

[There are, in us] possibilities that take our breath away, and show a world wider than either physics or philistine ethics can imagine. Here is a world in which all is well, in spite of certain forms of death, death of hope, death of strength, death of responsibility, of fear and wrong, death of everything that paganism, naturalism and legalism pin their trust on.

Whatever thought grips the mind at the time of death is the one which will propel it and decide for it the nature of its future birth. Thus if one wants to attain god after death, one has to think of him steadfastly... This is not as simple as it sounds, for at the time of death the mind automatically flies to the thought of an object (i.e. money, love) which has possessed it during its sojourn in the world. Thus one must think of god constantly.