A Quote by Randy Rainbow

Related Quotes

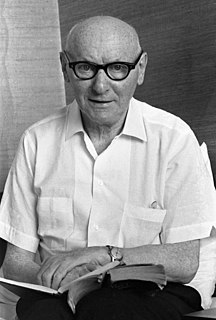

Even though I loved the song [My Yiddish Momme] and it was a sensational hit every time I sang it, I was always careful to use it only when I knew the majority of the house would understand Yiddish. However, you didn't have to be a Jew to be moved by 'My Yiddish Momme.' 'Mother' in any language means the same thing.

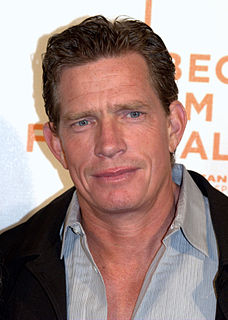

What happens when you speak colloquial Hebrew is you switch between registers all the time. So in a typical sentence, three words are biblical, one word is Russian, and one word is Yiddish. This kind of connection between very high language and very low language is very natural, people use it all the time.

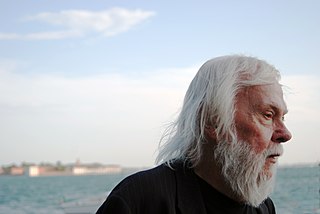

I have another aspect of my career where I'm a scholar of Yiddish and Hebrew literature, and I'll say that when you study Yiddish literature, you know a whole lot about forgotten writers. Most of the books on my shelves were literally saved from the garbage. I am sort of very aware of what it means to be a forgotten artist in that sense.

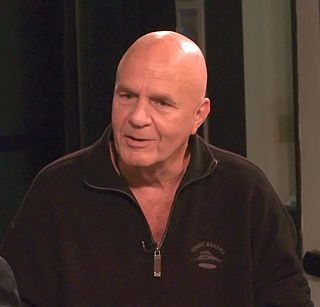

Yiddish, originally, in Eastern Europe was considered the language of children, of the illiterate, of women. And 500 years later, by the 19th century, by the 18th century, writers realized that, in order to communicate with the masses, they could no longer write in Hebrew. They needed to write in Yiddish, the language of the population.