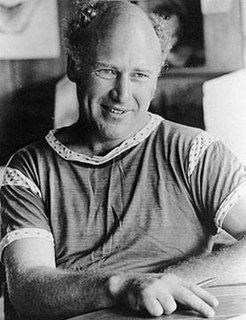

A Quote by Ray Bradbury

If I'd found out that Norman Mailer liked me. I'd have killed myself.

Related Quotes

It's always an interesting question of what was it like as Norman Mailer's son because I could easily turn it back and say what's it like not to. I didn't always realize my dad was Norman Mailer. I always knew he was Dad, and then I forget the exact age when it dawned on me that, you know, he is actually someone who affects the public consciousness of the time. It was amazing. I mean he was a rock star and brilliant and kind and funny and generous and scary when he needed to be and, you know, hard as a father.

After we did [All In The Family], that ended up being a real love fest all around. Me and Norman, Norman [Lear] and me, Rob Reiner, everybody liked everybody. So about six or seven months later I moved out to L.A. and I got a call that Norman wanted to see me. I came in and he said "ABC has given me a property that they just optioned to make into a TV series. It's from a play called Hot L Baltimore, and I want you to be in it."

The experience of climbing Kilimanjaro affected me so powerfully that, for a long time afterward, if I caught myself saying, "I'm not a person who likes to do that activity, eat that food, listen to that music," I would automatically go out and do what I imagined I didn't like. Generally I found I was wrong about myself - I liked what I thought I wouldn't like. And even if I didn't like the particular experience, I learned I liked having new experiences.