A Quote by Reginald Horace Blyth

It is not merely the brevity by which the haiku isolates a particular group of phenomena from all the rest; nor its suggestiveness, through which it reveals a whole world of experience. It is not only in its remarkable use of the season word, by which it gives us a feeling of a quarter of the year; nor its faint all-pervading humour. Its peculiar quality is its self-effacing, self-annihilative nature, by which it enables us, more than any other form of literature, to grasp the thing-in-itself.

Related Quotes

In this external world, which is full of finite things, it is impossible to see and find the Infinite. The Infinite must be sought in that alone which is infinite, and the only thing infinite about us is that which is within us, our own soul. Neither the body, nor the mind, nor even our thoughts, nor the world we see around us, is infinite.

There is a form of eminence which does not depend on fate; it is an air which sets us apart and seems to prtend great things; it is the value which we unconsciously attach to ourselves; it is the quality which wins us deference of others; more than birth, position, or ability, it gives us ascendance.

Many of our miseries are merely comparative: we are often made unhappy, not by the presence of any real evil, but by the absence of some fictitious good; of something which is not required by any real want of nature, which has not in itself any power of gratification, and which neither reason nor fancy would have prompted us to wish, did we not see it in the possession of others.

All the wants which disturb human life, which make us uneasy to ourselves, quarrelsome with others, and unthankful to God, which weary us in vain labors and foolish anxieties, which carry us from project to project, from place to place in a poor pursuit of we don't know what, are the wants which neither God, nor nature, nor reason hath subjected us to, but are solely infused into us by pride, envy, ambition, and covetousness.

The daimonic refers to the power of nature rather than the superego, and is beyond good and evil. Nor is it man's 'recall to himself' as Heidegger and later Fromm have argued, for its source lies in those realms where the self is rooted in natural forces which go beyond the self and are felt as the grasp of fate upon us. The daimonic arises from the ground of being rather than the self as such.

I have neither the scholar's melancholy, which is emulation; nor the musician's, which is fantastical; nor the courtier's, which is proud; not the soldier's which is ambitious; nor the lawyer's, which is politic; nor the lady's, which is nice; nor the lover's, which is all these: but it is a melancholy of mine own, compounded of many simples, extracted from many objects, and indeed the sundry contemplation of my travels, which, by often rumination, wraps me in a most humorous sadness.

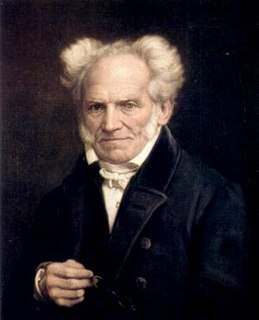

Poetry is related to philosophy as experience is related to empirical science. Experience makes us acquainted with the phenomenon in the particular and by means of examples, science embraces the whole of phenomena by means of general conceptions. So poetry seeks to make us acquainted with the Platonic Ideas through the particular and by means of examples. Philosophy aims at teaching, as a whole and in general, the inner nature of things which expresses itself in these. One sees even here that poetry bears more the character of youth, philosophy that of old age.

Humility has nothing to do with depreciating ourselves and our gifts in ways we know to be untrue. Even "humble" attitudes can be masks of pride. Humility is that freedom from our self which enables us to be in positions in which we have neither recognition nor importance, neither power nor visibility, and even experience deprivation, and yet have joy and delight. It is the freedom of knowing that we are not in the center of the universe, not even in the center of our own private universe.

Humility is often only the putting on of a submissiveness by which men hope to bring other people to submit to them; it is a morecalculated sort of pride, which debases itself with a design of being exalted; and though this vice transform itself into a thousand several shapes, yet the disguise is never more effectual nor more capable of deceiving the world than when concealed under a form of humility.

The total quantity of all the forces capable of work in the whole universe remains eternal and unchanged throughout all their changes. All change in nature amounts to this, that force can change its form and locality, without its quantity being changed. The universe possesses, once for all, a store of force which is not altered by any change of phenomena, can neither be increased nor diminished, and which maintains any change which takes place on it.

All thought of something is at the same time self-consciousness [...] At the root of all our experiences and all our reflections, we find [...] a being which immediately recognises itself, [...] and which knows its own existence, not by observation and as a given fact, nor by inference from any idea of itself, but through direct contact with that existence. Self-consciousness is the very being of mind in action.

Being established in my life, buttressed by my thinking nature, fastened down in this transcendental field which was opened for me by my first perception, and in which all absence is merely the obverse of a presence, all silence a modality of the being of sound, I enjoy a sort of ubiquity and theoretical eternity, I feel destined to move in a flow of endless life, neither the beginning nor the end of which I can experience in thought, since it is my living self who think of them, and since thus my life always precedes and survives itself.