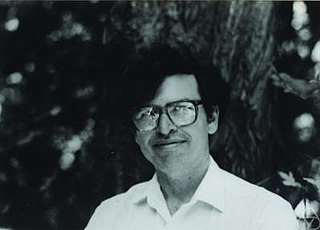

A Quote by Richard P. Feynman

The electron is a theory we use; it is so useful in understanding the way nature works that we can almost call it real.

Related Quotes

... landscapes or still-lifes I paint in between the abstract works; they constitute about one-tenth of my production. On the one hand they are useful, because I like to work from nature - although I do use a photograph - because I think that any detail from nature has a logic I would like to see in abstraction as well.

Can a physicist visualize an electron? The electron is materially inconceivable and yet, it is so perfectly known through its effects that we use it to illuminate our cities, guide our airlines through the night skies and take the most accurate measurements. What strange rationale makes some physicists accept the inconceivable electrons as real while refusing to accept the reality of a Designer on the ground that they cannot conceive Him?

You can call it tathata, suchness. 'Suchness' is a Buddhist way of expressing that there is something in you which always remains in its intrinsic nature, never changing. It always remains in its selfsame essence, eternally so. That is your real nature. That which changes is not you, that is mind. That which does not change in you is buddha-mind. You can call it no-mind, you can call it samadhi, satori. It depends upon you; you can give it whatsoever name you want. You can call it christ-consciousness.

Next, 'real' is what we may call a trouser-word. It is usually thought, and I dare say usually rightly thought, that what one might call the affirmative use of a term is basic--that, to understand 'x,' we need to know what it is to be x, or to be an x, and that knowing this apprises us of what it is not to be x, not to be an x. But with 'real' (as we briefly noted earlier) it is the negative use that wears the trousers.

I believe that almost all important, useful ideas are simple. Peter Whittle has recently put it nicely in an autobiographical essay. "If a piece of work is heavy and complicated then it is wrong." . . . Some writers feel that to express their ideas in simple terms is degrading. Some use complexity to disguise the paucity of their material. In fact, simplicity is a virtue and when, as here, it is both original and useful, it can represent a real advance in knowledge.

A successful unification of quantum theory and relativity would necessarily be a theory of the universe as a whole. It would tell us, as Aristotle and Newton did before, what space and time are, what the cosmos is, what things are made of, and what kind of laws those things obey. Such a theory will bring about a radical shift - a revolution - in our understanding of what nature is. It must also have wide repercussions, and will likely bring about, or contribute to, a shift in our understanding of ourselves and our relationship to the rest of the universe.