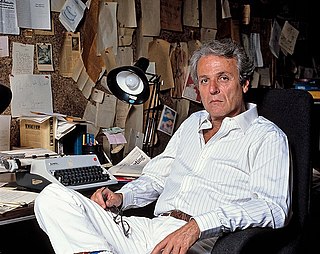

A Quote by Richard P. Feynman

There are theoretical physicists who imagine, deduce, and guess at new laws, but do not experiment; and then there are experimental physicists who experiment, imagine, deduce, and guess.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

The principle of science, the definition, almost, is the following: The test of all knowledge is experiment. Experiment is the sole judge of scientific "truth." But what is the source of knowledge? Where do the laws that are to be tested come from? Experiment, itself, helps to produce these laws, in the sense that it gives us hints. But also needed is imagination to create from these hints the great generalizations--to guess at the wonderful, simple, but very strange patterns beneath them all, and then to experiment to check again whether we have made the right guess.

If you look at the last 150 years, about every 30 years or so, a new scientific discipline emerges that starts spinning out technologies and capturing people's imaginations. Go back to 1900: That industry was chemistry. People had chemistry sets. In the 1930s, it was the rise of physics and physicists. They build on each other. Chemists laid the experimental understanding for the physicists to build their theories. It was three physicists who invented the transistor in 1947. That started the information revolution. Today, kids get computers.

I recognize that many physicists are smarter than I am-most of them theoretical physicists. A lot of smart people have gone into theoretical physics, therefore the field is extremely competitive. I console myself with the thought that although they may be smarter and may be deeper thinkers than I am, I have broader interests than they have.

Physicists only talk to physicists, economists to economists-worse still, nuclear physicists only talk to nuclear physicists and econometricians to econometricians. One wonders sometimes if science will not grind to a stop in an assemblage of walled-in hermits, each mumbling to himself words in a private language that only he can understand.

I'm convinced that a controlled disrespect for authority is essential to a scientist. All the good experimental physicists I have known have had an intense curiosity that no Keep Out sign could mute. Physicists do, of course, show a healthy respect for High Voltage, Radiation, and Liquid Hydrogen signs. They are not reckless. I can think of only six who have been killed on the job.

Physics has entered a remarkable era. Ideas that were once the realm of science fiction are now entering our theoretical ? and maybe even experimental ? grasp. Brand-new theoretical discoveries about extra dimensions have irreversibly changed how particle physicists, astrophysicists, and cosmologists now think about the world. The sheer number and pace of discoveries tells us that we've most likely only scratched the surface of the wondrous possibilities that lie in store. Ideas have taken on a life of their own.

To learn anything other than the stuff you find in books, you need to be able to experiment, to make mistakes, to accept feedback, and to try again. It doesn't matter whether you are learning to ride a bike or starting a new career, the cycle of experiment, feedback, and new experiment is always there.

It is quite true that many scientists, many physicists, maintain that the physical constants, the half dozen or so numbers that physicists have to simply assume in order to derive the rest of their understanding ... have to be assumed. You can't provide a rationale for why those numbers are there. Physicists have calculated that if any of these numbers was a little bit different, the universe as we know it wouldn't exist.

When chemists have brought their knowledge out of their special laboratories into the laboratory of the world, where chemical combinations are and have been through all time going on in such vast proportions,-when physicists study the laws of moisture, of clouds and storms, in past periods as well as in the present,-when, in short, geologists and zoologists are chemists and physicists, and vice versa,-then we shall learn more of the changes the world has undergone than is possible now that they are separately studied.

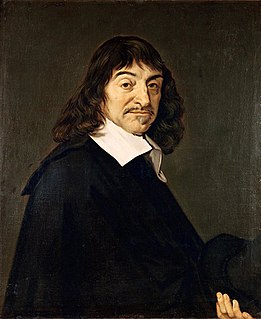

If we possessed a thorough knowledge of all the parts of the seed of any animal (e.g. man), we could from that alone, be reasons entirely mathematical and certain, deduce the whole conformation and figure of each of its members, and, conversely if we knew several peculiarities of this conformation, we would from those deduce the nature of its seed.