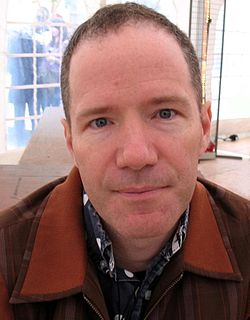

A Quote by Rick Moody

Maybe when I'm sixty-five I'll talk about my literary life.

Related Quotes

Sixty-five days principle photography, five-day weeks, which is the only way I'll work. With my cinematographer Russell Boyd, we take as much time as possible before pre-production, looking at stills. The next most important thing: he will come to me and talk about lenses. And I'll see his plan, which is generally great, and I might talk about how the light will be, handheld or not? I talk very freely, and try not to talk specifically, just talk around it, because it can unlock all sorts of things.

It is a hard thing when one has shot sixty-five lions or more, as I have in the course of my life, that the sixty-sixth should chew your leg like a quid of tobacco. It breaks the routine of the thing, and putting other considerations aside, I am an orderly man and don't like that. This is by the way.

[Michael] Chabon, who is himself a brash and playful and ebullient genre-bender, writes about how our idea of what constitutes literary fiction is a very narrow idea that, world-historically, evolved over the last sixty or seventy years or so - that until the rise of that kind of third-person-limited, middle-aged-white-guy-experiencing-enlightenment story as in some way the epitome of literary fiction - before that all kinds of crazy things that we would now define as belonging to genre were part of the literary canon.