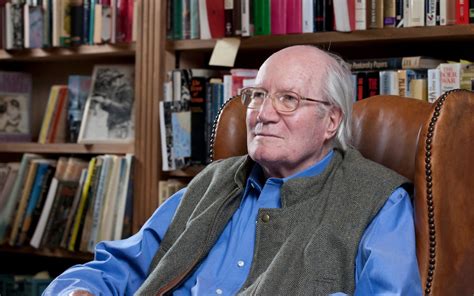

A Quote by Robert Fisk

I don't like the definition 'war correspondent'. It is history, not journalism, that has condemned the Middle East to war. I think 'war correspondent' smells a bit, reeks of false romanticism: it has too much of the whiff of Victorian reporters who would view battles from hilltops in the company of ladies, immune to suffering, only occasionally glancing towards the distant pop-pop of cannon fire.

Related Quotes

I think the public is very reluctant to get involved in more foreign wars, especially in the Middle East. And they understand, implicitly, that we go to war in the Middle East because of oil. And if we don't want to go to war in the Middle East, then we have to do something about the oil problem. And I think that view is gaining ground in the U.S.

My father was a little frightening - a huge man, six foot four - and he looked like God. He was always a visitor, as far as I was concerned, because my parents separated when I was nine. We only became friends when he was old and began to shrink. During the war, he was a BBC war correspondent and did some extraordinary broadcasts.

You have only to play at Little Wars three or four times to realize just what a blundering thing Great War must be. Great War is at present, I am convinced, not only the most expensive game in the universe, but it is a game out of all proportion. Not only are the masses of men and material and suffering and inconvenience too monstrously big for reason, but-the available heads we have for it, are too small. That, I think, is the most pacific realization conceivable, and Little War brings you to it as nothing else but Great War can do.

One of the reasons it's important for me to write about war is I really think that the concept of war, the specifics of war, the nature of war, the ethical ambiguities of war, are introduced too late to children. I think they can hear them, understand them, know about them, at a much younger age without being scared to death by the stories.

Every generation has its war. I have just been reminded of mine. It ended in 1989, 43 years after it began, the longest war Britain fought and certainly the most expensive. Its climax was total victory. Yet there was no parade, no medals, no colours hung in cathedrals. The Cold War saw no battles and cost almost no blood. Where there is no blood there is no glory and hence no history. Asked What did you do in the war, Daddy?, I could say only that I paid my taxes and left it at that.

We are constantly trying to cope with what our fathers or our grandfathers did. I wrote the book 'Great War of Civilization,' and my father was a solider in the First World War which produced the current Middle East - not that he had much to do with that - but he fought in what he believed was the Great War for Civilization.