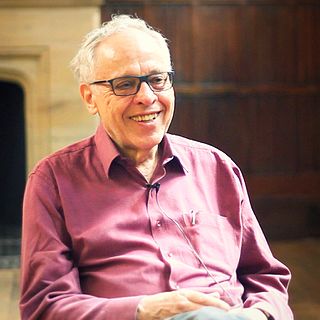

A Quote by Robert J. Shiller

That's the world we live in: when it comes to economics, people have emotions; it's not like chemistry or physics.

Related Quotes

Food, like anything else, lives in the physical world and obeys the laws of physics. When you whisk together some oil and a little bit of lemon juice - or, in other words, make mayonnaise - you are using the principles of physics and chemistry. Understanding how those principles affect cooking lets you cook better.

The information contained in an English sentence or computer software does not derive from the chemistry of the ink or the physics of magnetism, but from a source extrinsic to physics and chemistry altogether. Indeed, in both cases, the message transcends the properties of the medium. The information in DNA also transcends the properties of its material medium.

Did chemistry theorems exist? No: therefore you had to go further, not be satisfied with the quia, go back to the origins, to mathematics and physics. The origins of chemistry were ignoble, or at least equivocal: the dens of the alchemists, their abominable hodgepodge of ideas and language, their confessed interest in gold, their Levantine swindles typical of charlatans and magicians; instead, at the origin of physics lay the strenuous clarity of the West-Archimedes and Euclid.