A Quote by Robert Lucas, Jr.

The central predictions of the quantity theory are that, in the long run, money growth should be neutral in its effects on the growth rate of production and should affect the inflation rate on a one-for-one basis.

Related Quotes

Significant changes in the growth rate of money supply, even small ones, impact the financial markets first. Then, they impact changes in the real economy, usually in six to nine months, but in a range of three to 18 months. Usually in about two years in the US, they correlate with changes in the rate of inflation or deflation."

"The leads are long and variable, though the more inflation a society has experienced, history shows, the shorter the time lead will be between a change in money supply growth and the subsequent change in inflation.

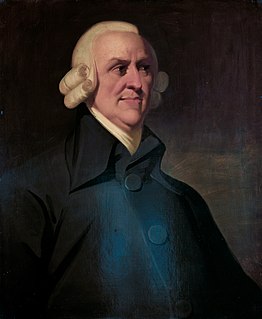

Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output... A steady rate of monetary growth at a moderate level can provide a framework under which a country can have little inflation and much growth. It will not produce perfect stability; it will not produce heaven on earth; but it can make an important contribution to a stable economic society.

The rate of growth of the relevant population is much greater than the rate of growth in funds, though funds have gone up very nicely. But we have been producing students at a rapid rate; they're competing for funds and therefore they're more frustrated. I think there's a certain sense of weariness in the intellectual realm, it's not in any way peculiar to economics, it's a general proposition.

What central banks can control is a base and one way they can control the base is via manipulating a particular interest rate, such as a Federal Funds rate, the overnight rate at which banks lend to one another. But they use that control to control what happens to the quantity of money. There is no disagreement.

My monetary studies have led me to the conclusion that central banks could profitably be replaced by computers geared to provide a steady rate of growth in the quantity of money. Fortunately for me personally, and for a select group of fellow economists, that conclusion has had no practical impact… else there would have been no Central Bank of Sweden to have established the award [Nobel Prize] I am honoured to receive.

The growth of the American food industry will always bump up against this troublesome biological fact: Try as we might, each of us can only eat about fifteen hundred pounds of food a year. Unlike many other products - CDs, say, or shoes - there's a natural limit to how much food we each can consume without exploding. What this means for the food industry is that its natural rate of growth is somewhere around 1 percent per year - 1 percent being the annual growth rate of American population. The problem is that [the industry] won't tolerate such an anemic rate of growth.