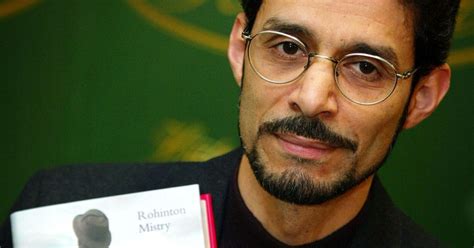

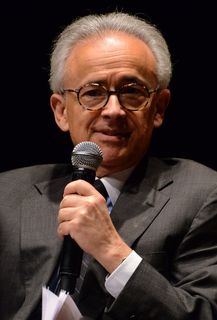

A Quote by Rohinton Mistry

In the broad sense, as a processing of everything one hears or witnesses, all fiction is autobiographical - imagination ground through the mill of memory. It's impossible to separate the two ingredients.

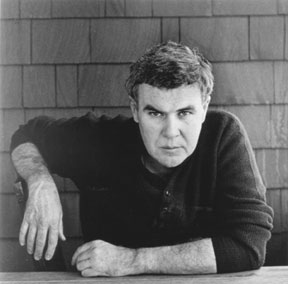

Related Quotes

Memory is like fiction; or else it's fiction that's like memory. This really came home to me once I started writing fiction, that memory seemd a kind of fiction, or vice versa. Either way, no matter how hard you try to put everything neatly into shape, the context wanders this way and that, until finally the context isn't even there anymore... Warm with life, hopeless unstable.

As you may know, my motto is: "All memory is fiction." It could just as easily be: "All fiction is memory." Unpacked, these two statements defy the ease of logic, but offer some really important truths about narrative art, at the very least, and about memory. So I would say that all art is personal.

There's basically an element of fiction in everything you remember. Imagination and memory are almost the same brain processes. When I write fiction, I know that I'm using a bunch of lies that I've made up to create some form of truth. When I write a memoir, I'm using true elements to create something that will always be somehow fictionalized.