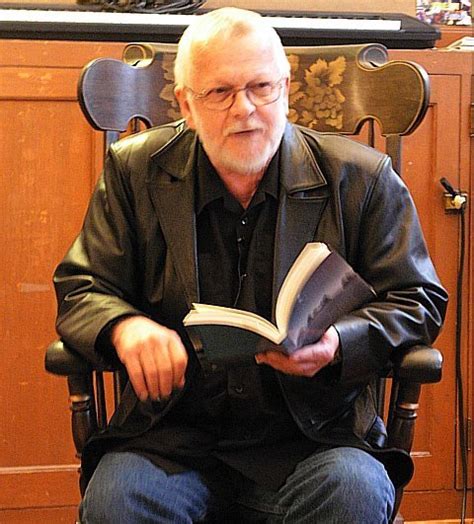

A Quote by Sam Hamill

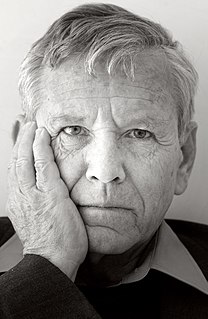

One of the things I love about translation is it obliterates the self. When I'm trying to figure out what Tu Fu has to say, I have to kind of impersonate Tu Fu. I have to take on, if you will, his voice and his skin in English, and I have to try to get as deeply into the poem as possible. I'm not trying to make an equivalent poem in English, which can't be done because our language can't accommodate the kind of metaphors within metaphors the Chinese written language can, and often does, contain.

Quote Topics

Related Quotes

Ho Kyuns poetry is in the tradition of his master, the incomparable Tu Fu, while remaining fully his own. Writing nine centuries later, Hos poetry strikes many parallels--the experiences of war and exile and constant struggle-- and his voice is similarly humane. This is rich and enlightening reading.

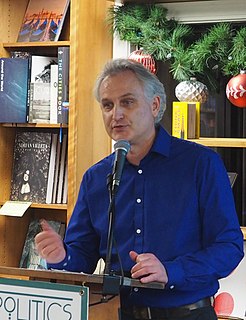

Some stories I write in Swedish, some in English. Short stories I've almost exclusively written in English lately, mostly because there's such a small market for them in Sweden and it doesn't really pay either. So, the translation goes both ways. What also factors in is that I have a different voice in English, which means that a straight translation wouldn't be the same as if I'd written it in English originally.

I have a funny relationship to language. When I came to California when I was three I spoke Urdu fluently and I didn't speak a word of English. Within a few months I lost all my Urdu and spoke only English and then I learned Urdu all over again when I was nine. Urdu is my first language but it's not as good as my English and it's sort of become my third language. English is my best language but was the second language I learned.

I spent ten years in London; I trained there. But because I started in English, it kind of feels the most natural to me, to act in English, which is a strange thing. My language is Spanish; I grew up in Argentina. I speak to my family in Spanish, but if you were to ask me what language I connect with, it'd be English in some weird way.

I think in Arabic at times, but when I'm writing it's all in English. And I don't try to make my English sound more Arabic, because it would be phony - I'm imagining Melanie Griffith trying to do a German accent in Shining Through. It just wouldn't work. But the language in my head is a specific kind of English. It's not exactly American, not exactly British. Because everything is filtered through me, through my experience. I'm Lebanese, but not that much. American, but not that much. Gay, but not that much. The only thing I'm sure of, really, is that I'm under 5'7".

We do not for example say that the person has a perfect knowledge of some language L similar to English but still different from it. What we say is that the child or foreigner has a 'partial knowledge of English' or is 'on his or her way' towards acquiring knowledge of English, and if they reach this goal, they will then know English.

James Joyce's English was based on the rhythm of the Irish language. He wrote things that shocked English language speakers but he was thinking in Gaelic. I've sung songs that if they were in English, would have been banned too. The psyche of the Irish language is completely different to the English-speaking world.

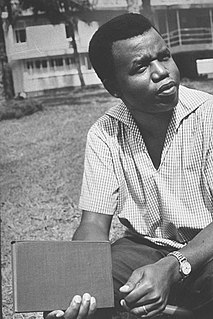

The price a world language must be prepared to pay is submission to many different kinds of use. The African writer should aim to use English in a way that brings out his message best without altering the language to the extent that its value as a medium of international exchange will be lost. He should aim at fashioning out an English which is at once universal and able to carry his peculiar experience.

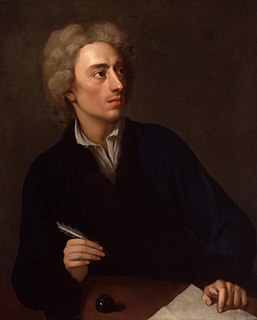

Translation is a kind of transubstantiation; one poem becomes another. You can choose your philosophy of translation just as you choose how to live: the free adaptation that sacrifices detail to meaning, the strict crib that sacrifices meaning to exactitude. The poet moves from life to language, the translator moves from language to life; both, like the immigrant, try to identify the invisible, what's between the lines, the mysterious implications.