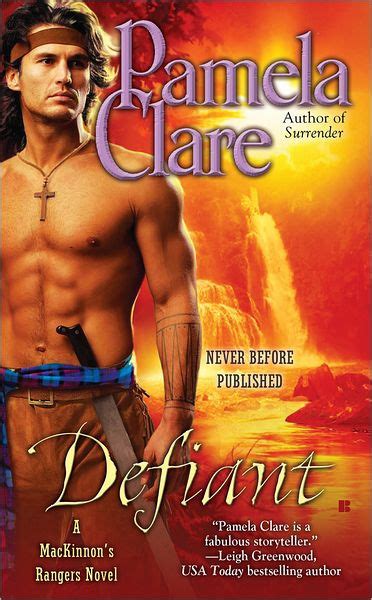

A Quote by Samuel Goldwyn

This book has too much plot and not enough story.

Related Quotes

Too many writers think that all you need to do is write well-but that's only part of what a good book is. Above all, a good book tells a good story. Focus on the story first. Ask yourself, 'Will other people find this story so interesting that they will tell others about it?' Remember: A bestselling book usually follows a simple rule, 'It's a wonderful story, wonderfully told'; not, 'It's a wonderfully told story.'

I have this very moment finished reading a novel called The Vicar of Wakefield [by Oliver Goldsmith].... It appears to me, to be impossible any person could read this book through with a dry eye and yet, I don't much like it.... There is but very little story, the plot is thin, the incidents very rare, the sentiments uncommon, the vicar is contented, humble, pious, virtuous--but upon the whole the book has not at all satisfied my expectations.

I always write a draft version of the novel in which I try to develop, not the story, not the plot, but the possibilities of the plot. I write without thinking much, trying to overcome all kinds of self-criticism, without stopping, without giving any consideration to the style or structure of the novel, only putting down on paper everything that can be used as raw material, very crude material for later development in the story.

Now, almost twenty years since my last job in book publishing, I know that there are far more socially inept people in book than in magazine publishing. At the time, however, I just didn't feel I was enough: smart enough, savvy enough, well read enough, educated enough, charming enough. Much of this was probably because I was very naive, and didn't really know how to behave in an office. This made me a terrible assistant, which in turn made me a terrible junior book editor.